The Modern Language Association Awards Recognition to Michael Anesko and the Henry James Letters Project

Regardless of whether or not you have read a work of fiction by Henry James or watched a popular film based on novels like The Golden Bowl, The Wings of a Dove, and The Portrait of a Lady, you will most likely have heard of him. A world-renowned American author who lived most of his life in England, becoming a British subject in 1915, James’ novels are celebrated for their expatriate themes and stylistic innovations. His work is still studied and read by a number of audiences, from scholars to students, and because of James’ reputation as a man who tested the limits of genres, he is recognized not only by readers everywhere, but also by organizations such as the Modern Language Association (MLA) whose Committee on Scholarly Editions lends their seal of approval to volumes deemed to have been edited according to the most exacting standards. Such recognition was bestowed at the recent MLA Convention held in Seattle, WA on recently published volumes of the Henry James Letters Project, for which Penn State Professor of English Michael Anesko serves as Co-General Editor. To receive the MLA’s official endorsement is no small feat. Such an honor represents the validity of the letters project and the association’s appreciation for the careful editorial process that Professor Anesko and his graduate research assistants adhere to in order to make James’ letters available to the reading public, many for the first time.

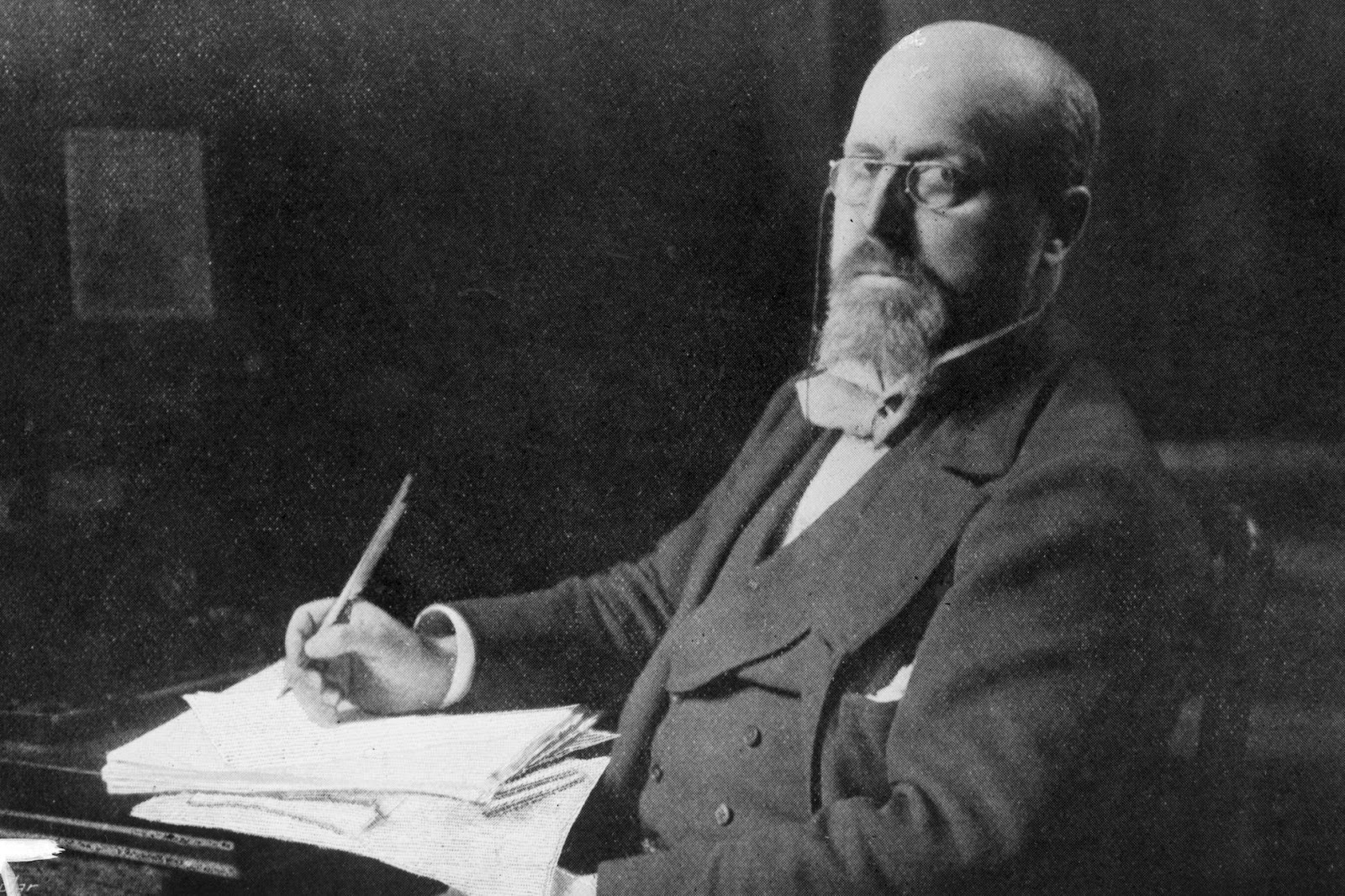

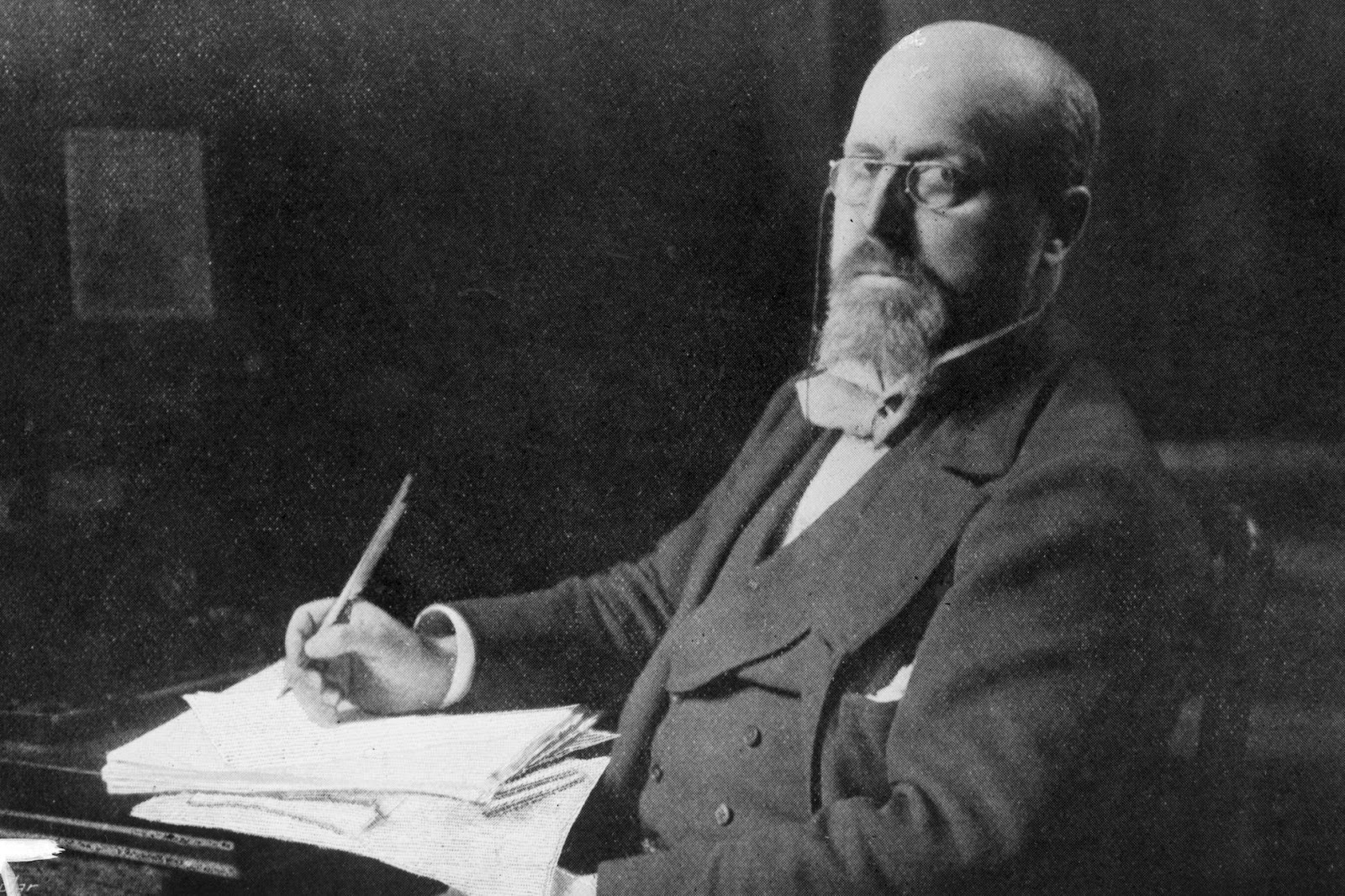

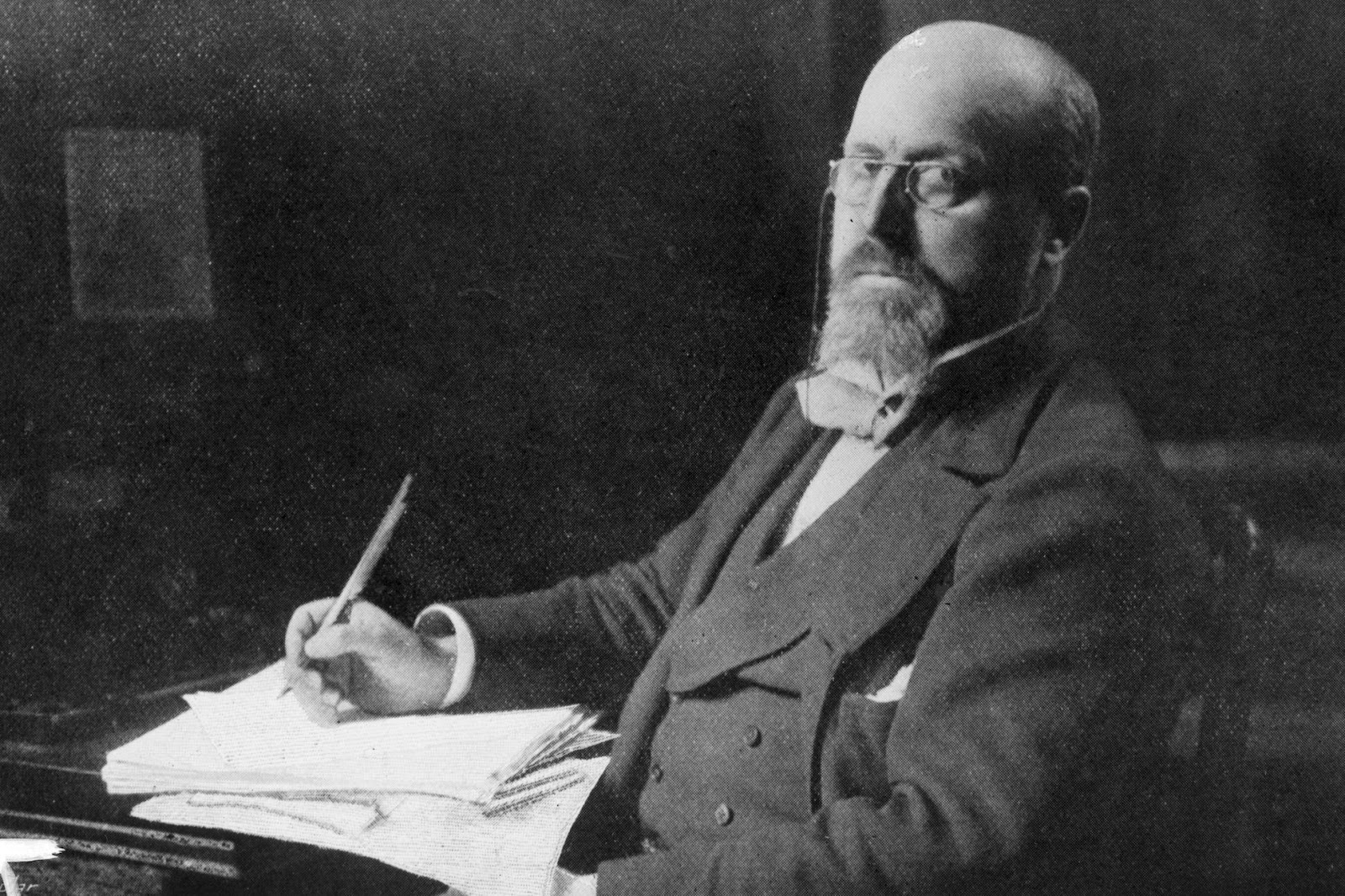

- Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The Henry James Letters Project, co-general edited by Professor Anesko and Greg Zacharias at Creighton University, was undertaken, in part, in the hopes of correcting earlier published editions of select James’ letters tainted by inaccurate transcriptions and editors who often had underlying motivations informing what they believed should and shouldn't be known about James or his correspondents. For example, past editors have omitted passages from letters in the hope that the material wouldn’t embarrass or compromise those mentioned. Censoring James’ letters in such a fashion, whether done innocently or not, doesn’t provide readers of his letters the full record of what James was writing about or what he truly wished to convey in his correspondence. Thus Professor Anesko, along with a team of graduate research assistants, is doing the hard work of accurately transcribing hundreds of letters over a multitude of years, with Professor Anesko having a hand in five of the thirteen volumes published to date, including introducing them and serving as their co-editor. He and his assistants review each and every letter thoroughly. According to Andrew Erlandson, a Penn State graduate student who currently serves as a research assistant for the James Letters Project, “every single letter included in these collections is read a minimum of four times to ensure the accuracy of the transcription.” As part of this review process, Anesko, Erlandson, and the other members of their editorial team provide relevant contextual notes as well as annotations for literary references in the letters. Altogether, the process is time-consuming but the collaboration between professors and students and between universities is an impressive and beneficial undertaking.

- Michael Anesko, Professor of English and American Studies

Professor Anesko, who in addition to editing James’ letters also serves as a General Editor of The Cambridge Edition of the Complete Fiction of Henry James, has read and reviewed more of James’ writings than most. Interviewing him about the award recognitions he has received for editorial work on James’ letters, I learned about the manifold challenges that come along with editing James’ letters. Through careful study and years of practice, one issue that Professor Anesko has learned to recognize and teach his graduate assistants to work through are the quirks in James’ penmanship. One of many bumps in the road to successfully transcribing and editing James’s letters, James’ confounding penmanship hardly causes Professor Anesko to lose his thrill and thirst for knowledge about how James approached and managed his correspondence with others. “The great pleasure for me now is coming across material that I’m not familiar with; discovering in those letters new sources of information and a delight in the actual wording of the letters”. One aspect of the project that especially excites Professor Anesko is the prospect of reading certain letters because of whom they are written for. For example, one correspondent of James’ named Grace Norton delights not only James, but also the editors. “It’s always a moment of mutual anticipation when we get to a letter that James wrote to his friend Grace Norton, a very dear friend from Cambridge, a woman who never married but was very intellectual and had an intense interior life. None of her letters to James survive. His habit was to burn them upon receiving them.” It’s correspondence with the likes of Grace Norton that reveals something about James we may not have ever known, Anesko suggests. The letters reveal what James' thought about himself and also how he coped with difficult events in his life, such as the death of his parents. Accordingly, the letters project allows readers to understand in new and richly important ways how James became the celebrated author and personality we read and study today.

- The Complete Letters of Henry James, 1883–1884, Volume 2

Another major challenge that this project has had to confront is a controversy surrounding the decision to publish James’ letters against his expressed wishes. More precisely, James never wanted his letters to be made public so as to protect his privacy and limit investigations into, and queries about, his life. When asked if he felt in any way uneasy about the letters project since he was publishing correspondence that was meant to die with James, Professor Anesko suggested that the issue was resolved a long time ago. Once recipients of James’ letters defied his instructions to burn the letters, they effectively decided against James’ wishes and provided the editors of the James Letters Project with the opportunity to make the letters available to the public. As a result, readers in the twenty-first century are provided access to dimensions of James’ personal and professional lives that would have otherwise been lost to history. We see not only Henry James the writer in the letters to his editors and publishers, but also the caring, questioning, and political James in letters addressed to family, friends, and other acquaintances. The amount of effort that has gone into the project is appreciated by all readers, from scholars to the general public, who, as Professor Anesko puts it, don’t think of the editors as “publishing scoundrels”, unlike the nameless character in James’ novella “The Aspern Papers”, which deals with issues of lost privacy and the hardships of fame.

- The Complete Letters of Henry James, 1884–1886: Volume 1

In terms of the longevity of the project, James wrote well over 10,000 letters, many of which remain to be edited and published in future volumes. When asked how long he sees himself continuing on as General Co-Editor, Anesko suggested that while he believes the project may continue beyond his lifetime, he has no plans to stop his editorial work with the James Letters Project anytime soon. Something that will soon change about the project is what he and his assistants will actually be editing. Currently, the team is editing James’ handwritten letters, but later in James’ life, with the advent of modern transcription technologies like the typewriter, James dictated his thoughts to his assistants. Because of that development, the editing of the letters in the months and years to come should proceed more quickly since the peculiarities of James’ handwriting will have been overwritten by typewritten text, making the letters much easier to read and edit. For all of us—Michael Anesko and his team of capable editors with the Henry James Letters Project and the many appreciative readers of their MLA-approved multivolume edition of James’ letters—it will be fascinating to see how technology alters not only how James communicated with others but also how we understand the multifaceted James conveyed to us by his letters.

Regardless of whether or not you have read a work of fiction by Henry James or watched a popular film based on novels like The Golden Bowl, The Wings of a Dove, and The Portrait of a Lady, you will most likely have heard of him. A world-renowned American author who lived most of his life in England, becoming a British subject in 1915, James’ novels are celebrated for their expatriate themes and stylistic innovations. His work is still studied and read by a number of audiences, from scholars to students, and because of James’ reputation as a man who tested the limits of genres, he is recognized not only by readers everywhere, but also by organizations such as the Modern Language Association (MLA) whose Committee on Scholarly Editions lends their seal of approval to volumes deemed to have been edited according to the most exacting standards. Such recognition was bestowed at the recent MLA Convention held in Seattle, WA on recently published volumes of the Henry James Letters Project, for which Penn State Professor of English Michael Anesko serves as Co-General Editor. To receive the MLA’s official endorsement is no small feat. Such an honor represents the validity of the letters project and the association’s appreciation for the careful editorial process that Professor Anesko and his graduate research assistants adhere to in order to make James’ letters available to the reading public, many for the first time.

- Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The Henry James Letters Project, co-general edited by Professor Anesko and Greg Zacharias at Creighton University, was undertaken, in part, in the hopes of correcting earlier published editions of select James’ letters tainted by inaccurate transcriptions and editors who often had underlying motivations informing what they believed should and shouldn't be known about James or his correspondents. For example, past editors have omitted passages from letters in the hope that the material wouldn’t embarrass or compromise those mentioned. Censoring James’ letters in such a fashion, whether done innocently or not, doesn’t provide readers of his letters the full record of what James was writing about or what he truly wished to convey in his correspondence. Thus Professor Anesko, along with a team of graduate research assistants, is doing the hard work of accurately transcribing hundreds of letters over a multitude of years, with Professor Anesko having a hand in five of the thirteen volumes published to date, including introducing them and serving as their co-editor. He and his assistants review each and every letter thoroughly. According to Andrew Erlandson, a Penn State graduate student who currently serves as a research assistant for the James Letters Project, “every single letter included in these collections is read a minimum of four times to ensure the accuracy of the transcription.” As part of this review process, Anesko, Erlandson, and the other members of their editorial team provide relevant contextual notes as well as annotations for literary references in the letters. Altogether, the process is time-consuming but the collaboration between professors and students and between universities is an impressive and beneficial undertaking.

- Michael Anesko, Professor of English and American Studies

Professor Anesko, who in addition to editing James’ letters also serves as a General Editor of The Cambridge Edition of the Complete Fiction of Henry James, has read and reviewed more of James’ writings than most. Interviewing him about the award recognitions he has received for editorial work on James’ letters, I learned about the manifold challenges that come along with editing James’ letters. Through careful study and years of practice, one issue that Professor Anesko has learned to recognize and teach his graduate assistants to work through are the quirks in James’ penmanship. One of many bumps in the road to successfully transcribing and editing James’s letters, James’ confounding penmanship hardly causes Professor Anesko to lose his thrill and thirst for knowledge about how James approached and managed his correspondence with others. “The great pleasure for me now is coming across material that I’m not familiar with; discovering in those letters new sources of information and a delight in the actual wording of the letters”. One aspect of the project that especially excites Professor Anesko is the prospect of reading certain letters because of whom they are written for. For example, one correspondent of James’ named Grace Norton delights not only James, but also the editors. “It’s always a moment of mutual anticipation when we get to a letter that James wrote to his friend Grace Norton, a very dear friend from Cambridge, a woman who never married but was very intellectual and had an intense interior life. None of her letters to James survive. His habit was to burn them upon receiving them.” It’s correspondence with the likes of Grace Norton that reveals something about James we may not have ever known, Anesko suggests. The letters reveal what James' thought about himself and also how he coped with difficult events in his life, such as the death of his parents. Accordingly, the letters project allows readers to understand in new and richly important ways how James became the celebrated author and personality we read and study today.

- The Complete Letters of Henry James, 1883–1884, Volume 2

Another major challenge that this project has had to confront is a controversy surrounding the decision to publish James’ letters against his expressed wishes. More precisely, James never wanted his letters to be made public so as to protect his privacy and limit investigations into, and queries about, his life. When asked if he felt in any way uneasy about the letters project since he was publishing correspondence that was meant to die with James, Professor Anesko suggested that the issue was resolved a long time ago. Once recipients of James’ letters defied his instructions to burn the letters, they effectively decided against James’ wishes and provided the editors of the James Letters Project with the opportunity to make the letters available to the public. As a result, readers in the twenty-first century are provided access to dimensions of James’ personal and professional lives that would have otherwise been lost to history. We see not only Henry James the writer in the letters to his editors and publishers, but also the caring, questioning, and political James in letters addressed to family, friends, and other acquaintances. The amount of effort that has gone into the project is appreciated by all readers, from scholars to the general public, who, as Professor Anesko puts it, don’t think of the editors as “publishing scoundrels”, unlike the nameless character in James’ novella “The Aspern Papers”, which deals with issues of lost privacy and the hardships of fame.

- The Complete Letters of Henry James, 1884–1886: Volume 1

In terms of the longevity of the project, James wrote well over 10,000 letters, many of which remain to be edited and published in future volumes. When asked how long he sees himself continuing on as General Co-Editor, Anesko suggested that while he believes the project may continue beyond his lifetime, he has no plans to stop his editorial work with the James Letters Project anytime soon. Something that will soon change about the project is what he and his assistants will actually be editing. Currently, the team is editing James’ handwritten letters, but later in James’ life, with the advent of modern transcription technologies like the typewriter, James dictated his thoughts to his assistants. Because of that development, the editing of the letters in the months and years to come should proceed more quickly since the peculiarities of James’ handwriting will have been overwritten by typewritten text, making the letters much easier to read and edit. For all of us—Michael Anesko and his team of capable editors with the Henry James Letters Project and the many appreciative readers of their MLA-approved multivolume edition of James’ letters—it will be fascinating to see how technology alters not only how James communicated with others but also how we understand the multifaceted James conveyed to us by his letters.