A Virtual Visit to Carlisle’s Archive Amplifies Forgotten Indigenous Stories

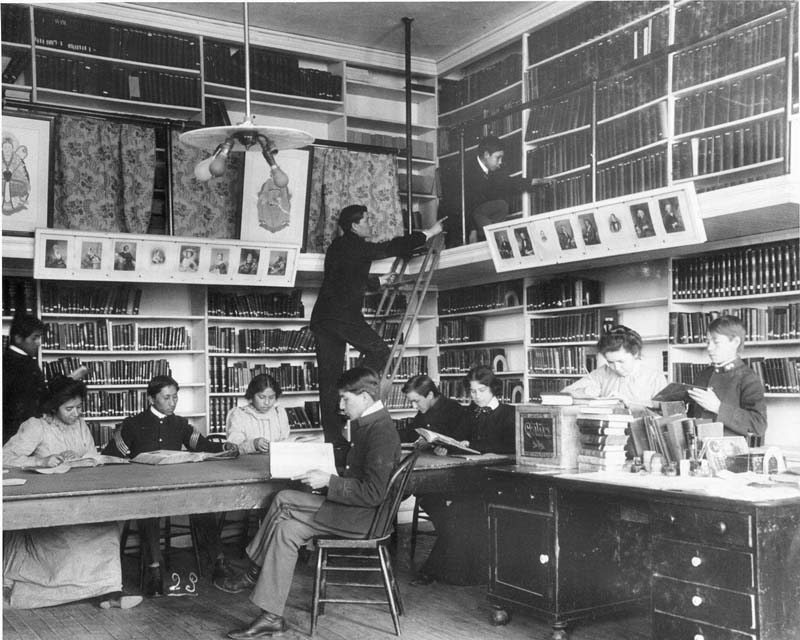

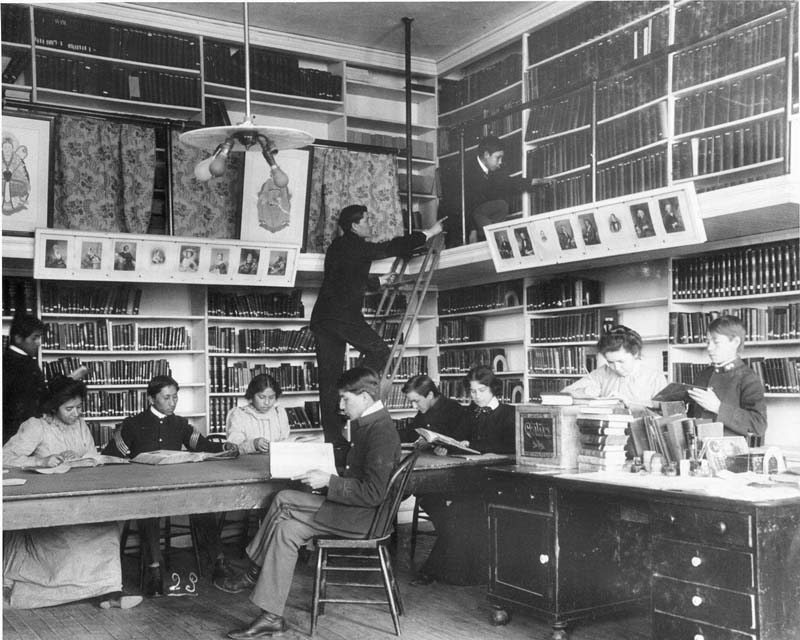

The past few months of Centre County Reads programming on Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants familiarized participants with local connections to Indigenous history, such as the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, which Kimmerer’s grandfather attended and whose grounds are only two hours away from State College. Carlisle today maintains a valuable archive that sheds light on the school’s efforts to assimilate Indigenous children and ultimately erase their culture. Fortunately, a physical visit isn’t necessary to engage with Carlisle’s materials, due to the efforts of librarians and professors at Dickinson College, who have digitized the school’s archive at the Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center (CISDRC). In lieu of traveling to the Carlisle School itself, a visit to the CISDRC can help the Centre County community continue to uncover the stories of Indigenous history and therefore continue to participate in Kimmerer’s project to recuperate Indigenous knowledge and experience.

Established in 2013 as a digital initiative of Dickinson College’s Archives and Special Collections, the CISDRC’s mission is to make Carlisle’s records digitally available for the general public and students alike. “I had the idea that it would be really helpful for a lot of people if this information could be more easily accessible online,” said Jim Gerencser, a librarian at Dickinson College who co-directs the CISDRC. Indeed, given the stunning wealth of materials composing Carlisle’s archive—Gerencser said there are about “300,000 pages of documentation” now digitized—the CISDRC makes it substantially easier to conduct research on the school. Amelia Katanski, whose book on Carlisle and Indigenous boarding schools, Learning to Write “Indian”: The Boarding School Experience and American Indian Literature, was written before the archives were digitized, is “grateful” for the CISDRC. “The digitization work that has happened since my book has transformed people's ability to do work in/educate about Carlisle and the boarding school era,” Katanski said.

Established in 2013 as a digital initiative of Dickinson College’s Archives and Special Collections, the CISDRC’s mission is to make Carlisle’s records digitally available for the general public and students alike. “I had the idea that it would be really helpful for a lot of people if this information could be more easily accessible online,” said Jim Gerencser, a librarian at Dickinson College who co-directs the CISDRC. Indeed, given the stunning wealth of materials composing Carlisle’s archive—Gerencser said there are about “300,000 pages of documentation” now digitized—the CISDRC makes it substantially easier to conduct research on the school. Amelia Katanski, whose book on Carlisle and Indigenous boarding schools, Learning to Write “Indian”: The Boarding School Experience and American Indian Literature, was written before the archives were digitized, is “grateful” for the CISDRC. “The digitization work that has happened since my book has transformed people's ability to do work in/educate about Carlisle and the boarding school era,” Katanski said.

One example of how the CISDRC enabled research on Carlisle comes from Dickinson College itself. In 2017, Professor Noreen Lape taught a class called “What Writers Matter? Multiculturalism in American Literature.” For their final project, students in the class collectively delved into the CISDRC to explore the work of fifteen Carlisle students. Their efforts culminated in the organization of a separate digital page called “Voices from the Carlisle Indian School.” Lape’s students found complex and surprising voices in the Carlisle student work they researched and read.

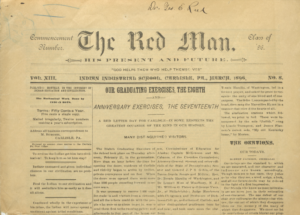

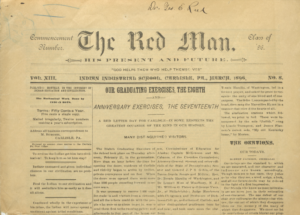

“We were looking at the various voices that popped up in the pieces: they had a literary magazine or a newspaper newsletter where the students published their work and then the founders of the school could show these off to potential donors and patrons, and we saw some subversive or resistant writing happening within them,” Lape said. The pieces are striking for how they complement the themes of Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass—most significantly, the recuperation and validation of Indigenous history and storytelling in the face of their suppression by the US.

One of these pieces, written by Elmira Jerome, concerns the Potawatomi people—an Indigenous nation that will be familiar to readers of Braiding Sweetgrass, as Kimmerer herself is a member of the Potawatomi. In her piece, Jerome recounts a legend of the Potawatomi’s origin. Kitchemanito, the Great Spirit, created a world inhabited by ungrateful beings who would not give thanks to him. In return, Kitchemanito punished these beings by remaking the world and populating it only with two humans, a brother and a sister. The latter marries Mondamin, a symbolization of maize, which allows for the sustenance of all humans thereafter. Ultimately, the story resonates with Kimmerer’s themes of reciprocity in Braiding Sweetgrass: the brother and sister respect Kitchemanito’s provision of a bountiful land and therefore are repaid by having plenty “to put into their cooking kettles along with their meat.”

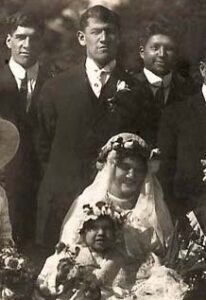

These ideas of reciprocity are also depicted in a piece written by Iva Miller—who met her future husband, the great Jim Thorpe, at Carlisle—called “Robin Red Breast.” Miller’s story centers on a captured warrior who is aided by a “little bird.” The bird succeeds in breaking the warrior’s fetters, but in doing so pokes through the warrior’s skin, and his blood “painted the little bird’s breast red,” which is “why certain robins of to-day have red breasts.” The relationship between the warrior and the robin illustrates the give-and-take dynamic of reciprocity; both the warrior and the robin leave their marks on each other. Readers of Braiding Sweetgrass may think of Skywoman in this regard, who indeed appears in other pieces by Carlisle students. Skywoman is a responsible partner to nature. As Kimmerer writes, when animals aid this “helpless human,” Skywoman responds with “deep gratitude” and reciprocity, recognizing that what is accepted from nature must also be given back.

These ideas of reciprocity are also depicted in a piece written by Iva Miller—who met her future husband, the great Jim Thorpe, at Carlisle—called “Robin Red Breast.” Miller’s story centers on a captured warrior who is aided by a “little bird.” The bird succeeds in breaking the warrior’s fetters, but in doing so pokes through the warrior’s skin, and his blood “painted the little bird’s breast red,” which is “why certain robins of to-day have red breasts.” The relationship between the warrior and the robin illustrates the give-and-take dynamic of reciprocity; both the warrior and the robin leave their marks on each other. Readers of Braiding Sweetgrass may think of Skywoman in this regard, who indeed appears in other pieces by Carlisle students. Skywoman is a responsible partner to nature. As Kimmerer writes, when animals aid this “helpless human,” Skywoman responds with “deep gratitude” and reciprocity, recognizing that what is accepted from nature must also be given back.

Jerome and Miller were categorized by Lape’s students as “Tribal Educators” to indicate their commitment to preserving and sharing Indigenous culture and history. Other Carlisle writers wrote pieces that explicitly took up the issue of how Indigenous people should confront US society. These writers were organized into three categories: “Assimilators,” “Resistors,” and “The Conflicted.” Keyword tags provide another layer of thematic organization, linking pieces across categories. Some of the most common keywords include “assimilation,” “Christianity,” “Origin Story,” and “white-Indian relations.”

Elmer Simon’s piece, “The Indian – A Man,” is a moving critique of the social inequalities faced by Indigenous people at the hands of white colonial settlers and their descendants. Though categorized as an “Assimilator,” Simon provides a counter history to the US’s own origin story. Addressing a white audience, Simon writes, “Your forefathers were cordially welcomed as guests, brothers and even Gods, with great hospitality, and the Indian remained as their best friend until their own, dangerous  intentions betrayed them.” Simon, like Kimmerer, thus contributes to a counter education that amplifies Indigenous experience, so often erased by US historical narratives. He recovers the dignity and humanity of his ancestors against a legacy of debasement and erasure perpetrated by the US.

intentions betrayed them.” Simon, like Kimmerer, thus contributes to a counter education that amplifies Indigenous experience, so often erased by US historical narratives. He recovers the dignity and humanity of his ancestors against a legacy of debasement and erasure perpetrated by the US.

Another student, Delos Lone Wolf, similarly critiqued US treatment of Indigenous peoples. His 1896 graduation speech is lost to history, but an oral account published in The Red Man—the Carlisle School’s student newspaper—preserves his remarks. He condemns reservations that have kept Indigenous people in “prison” and charges his graduating classmates to “direct your energies toward their advancement.” Though this idea was compatible with a Western “civilizing mission,” Lone Wolf amplifies the Indigenous perspective as a necessary component to a more just and equitable US society. In this way, he reflects Kimmerer’s call in her lecture culminating this year’s CCR programming for an approach to the natural world that blends Indigenous and Western knowledges.

By preserving all of these pieces, and thus enabling engagements with them, the CISDRC is, in Lape’s words, a “great contribution to American history.” As she explains, “There's so many things that you can find, voices you can recover, that enhance our understanding of Indigenous relations in the 19th century and the history of these schools. My class’s final project was an exercise in understanding and empathy but also scholarship and critical thinking.”

But that contribution is certainly not limited to Lape’s class. The work done by Lape’s students is just one example of how the CISDRC can enable us to project the voices of the Carlisle School’s victims and contribute to Kimmerer’s project to center Indigenous experience. It keeps the spotlight on the hardships these children—like Kimmerer’s grandfather—were forced to face. The legacy of this experience is preserved in a heartbreaking letter written by Minnie Tsait-Kopeta, begging her family to petition Carlisle to allow her to return home. “This life is too hard for me,” she writes. “I shall fail in health I am already failing.” The CISDRC has ensured that Tsait-Kopeta’s words will not remain silent, as long as we continue to read and remember them. We must keep her story alive, and stories of her classmates, in the same way that we must keep Kimmerer’s stories alive now that the CCR programming has ended.

The past few months of Centre County Reads programming on Robin Wall Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teachings of Plants familiarized participants with local connections to Indigenous history, such as the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, which Kimmerer’s grandfather attended and whose grounds are only two hours away from State College. Carlisle today maintains a valuable archive that sheds light on the school’s efforts to assimilate Indigenous children and ultimately erase their culture. Fortunately, a physical visit isn’t necessary to engage with Carlisle’s materials, due to the efforts of librarians and professors at Dickinson College, who have digitized the school’s archive at the Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center (CISDRC). In lieu of traveling to the Carlisle School itself, a visit to the CISDRC can help the Centre County community continue to uncover the stories of Indigenous history and therefore continue to participate in Kimmerer’s project to recuperate Indigenous knowledge and experience.

Established in 2013 as a digital initiative of Dickinson College’s Archives and Special Collections, the CISDRC’s mission is to make Carlisle’s records digitally available for the general public and students alike. “I had the idea that it would be really helpful for a lot of people if this information could be more easily accessible online,” said Jim Gerencser, a librarian at Dickinson College who co-directs the CISDRC. Indeed, given the stunning wealth of materials composing Carlisle’s archive—Gerencser said there are about “300,000 pages of documentation” now digitized—the CISDRC makes it substantially easier to conduct research on the school. Amelia Katanski, whose book on Carlisle and Indigenous boarding schools, Learning to Write “Indian”: The Boarding School Experience and American Indian Literature, was written before the archives were digitized, is “grateful” for the CISDRC. “The digitization work that has happened since my book has transformed people's ability to do work in/educate about Carlisle and the boarding school era,” Katanski said.

Established in 2013 as a digital initiative of Dickinson College’s Archives and Special Collections, the CISDRC’s mission is to make Carlisle’s records digitally available for the general public and students alike. “I had the idea that it would be really helpful for a lot of people if this information could be more easily accessible online,” said Jim Gerencser, a librarian at Dickinson College who co-directs the CISDRC. Indeed, given the stunning wealth of materials composing Carlisle’s archive—Gerencser said there are about “300,000 pages of documentation” now digitized—the CISDRC makes it substantially easier to conduct research on the school. Amelia Katanski, whose book on Carlisle and Indigenous boarding schools, Learning to Write “Indian”: The Boarding School Experience and American Indian Literature, was written before the archives were digitized, is “grateful” for the CISDRC. “The digitization work that has happened since my book has transformed people's ability to do work in/educate about Carlisle and the boarding school era,” Katanski said.

One example of how the CISDRC enabled research on Carlisle comes from Dickinson College itself. In 2017, Professor Noreen Lape taught a class called “What Writers Matter? Multiculturalism in American Literature.” For their final project, students in the class collectively delved into the CISDRC to explore the work of fifteen Carlisle students. Their efforts culminated in the organization of a separate digital page called “Voices from the Carlisle Indian School.” Lape’s students found complex and surprising voices in the Carlisle student work they researched and read.

“We were looking at the various voices that popped up in the pieces: they had a literary magazine or a newspaper newsletter where the students published their work and then the founders of the school could show these off to potential donors and patrons, and we saw some subversive or resistant writing happening within them,” Lape said. The pieces are striking for how they complement the themes of Kimmerer’s Braiding Sweetgrass—most significantly, the recuperation and validation of Indigenous history and storytelling in the face of their suppression by the US.

One of these pieces, written by Elmira Jerome, concerns the Potawatomi people—an Indigenous nation that will be familiar to readers of Braiding Sweetgrass, as Kimmerer herself is a member of the Potawatomi. In her piece, Jerome recounts a legend of the Potawatomi’s origin. Kitchemanito, the Great Spirit, created a world inhabited by ungrateful beings who would not give thanks to him. In return, Kitchemanito punished these beings by remaking the world and populating it only with two humans, a brother and a sister. The latter marries Mondamin, a symbolization of maize, which allows for the sustenance of all humans thereafter. Ultimately, the story resonates with Kimmerer’s themes of reciprocity in Braiding Sweetgrass: the brother and sister respect Kitchemanito’s provision of a bountiful land and therefore are repaid by having plenty “to put into their cooking kettles along with their meat.”

These ideas of reciprocity are also depicted in a piece written by Iva Miller—who met her future husband, the great Jim Thorpe, at Carlisle—called “Robin Red Breast.” Miller’s story centers on a captured warrior who is aided by a “little bird.” The bird succeeds in breaking the warrior’s fetters, but in doing so pokes through the warrior’s skin, and his blood “painted the little bird’s breast red,” which is “why certain robins of to-day have red breasts.” The relationship between the warrior and the robin illustrates the give-and-take dynamic of reciprocity; both the warrior and the robin leave their marks on each other. Readers of Braiding Sweetgrass may think of Skywoman in this regard, who indeed appears in other pieces by Carlisle students. Skywoman is a responsible partner to nature. As Kimmerer writes, when animals aid this “helpless human,” Skywoman responds with “deep gratitude” and reciprocity, recognizing that what is accepted from nature must also be given back.

These ideas of reciprocity are also depicted in a piece written by Iva Miller—who met her future husband, the great Jim Thorpe, at Carlisle—called “Robin Red Breast.” Miller’s story centers on a captured warrior who is aided by a “little bird.” The bird succeeds in breaking the warrior’s fetters, but in doing so pokes through the warrior’s skin, and his blood “painted the little bird’s breast red,” which is “why certain robins of to-day have red breasts.” The relationship between the warrior and the robin illustrates the give-and-take dynamic of reciprocity; both the warrior and the robin leave their marks on each other. Readers of Braiding Sweetgrass may think of Skywoman in this regard, who indeed appears in other pieces by Carlisle students. Skywoman is a responsible partner to nature. As Kimmerer writes, when animals aid this “helpless human,” Skywoman responds with “deep gratitude” and reciprocity, recognizing that what is accepted from nature must also be given back.

Jerome and Miller were categorized by Lape’s students as “Tribal Educators” to indicate their commitment to preserving and sharing Indigenous culture and history. Other Carlisle writers wrote pieces that explicitly took up the issue of how Indigenous people should confront US society. These writers were organized into three categories: “Assimilators,” “Resistors,” and “The Conflicted.” Keyword tags provide another layer of thematic organization, linking pieces across categories. Some of the most common keywords include “assimilation,” “Christianity,” “Origin Story,” and “white-Indian relations.”

Elmer Simon’s piece, “The Indian – A Man,” is a moving critique of the social inequalities faced by Indigenous people at the hands of white colonial settlers and their descendants. Though categorized as an “Assimilator,” Simon provides a counter history to the US’s own origin story. Addressing a white audience, Simon writes, “Your forefathers were cordially welcomed as guests, brothers and even Gods, with great hospitality, and the Indian remained as their best friend until their own, dangerous  intentions betrayed them.” Simon, like Kimmerer, thus contributes to a counter education that amplifies Indigenous experience, so often erased by US historical narratives. He recovers the dignity and humanity of his ancestors against a legacy of debasement and erasure perpetrated by the US.

intentions betrayed them.” Simon, like Kimmerer, thus contributes to a counter education that amplifies Indigenous experience, so often erased by US historical narratives. He recovers the dignity and humanity of his ancestors against a legacy of debasement and erasure perpetrated by the US.

Another student, Delos Lone Wolf, similarly critiqued US treatment of Indigenous peoples. His 1896 graduation speech is lost to history, but an oral account published in The Red Man—the Carlisle School’s student newspaper—preserves his remarks. He condemns reservations that have kept Indigenous people in “prison” and charges his graduating classmates to “direct your energies toward their advancement.” Though this idea was compatible with a Western “civilizing mission,” Lone Wolf amplifies the Indigenous perspective as a necessary component to a more just and equitable US society. In this way, he reflects Kimmerer’s call in her lecture culminating this year’s CCR programming for an approach to the natural world that blends Indigenous and Western knowledges.

By preserving all of these pieces, and thus enabling engagements with them, the CISDRC is, in Lape’s words, a “great contribution to American history.” As she explains, “There's so many things that you can find, voices you can recover, that enhance our understanding of Indigenous relations in the 19th century and the history of these schools. My class’s final project was an exercise in understanding and empathy but also scholarship and critical thinking.”

But that contribution is certainly not limited to Lape’s class. The work done by Lape’s students is just one example of how the CISDRC can enable us to project the voices of the Carlisle School’s victims and contribute to Kimmerer’s project to center Indigenous experience. It keeps the spotlight on the hardships these children—like Kimmerer’s grandfather—were forced to face. The legacy of this experience is preserved in a heartbreaking letter written by Minnie Tsait-Kopeta, begging her family to petition Carlisle to allow her to return home. “This life is too hard for me,” she writes. “I shall fail in health I am already failing.” The CISDRC has ensured that Tsait-Kopeta’s words will not remain silent, as long as we continue to read and remember them. We must keep her story alive, and stories of her classmates, in the same way that we must keep Kimmerer’s stories alive now that the CCR programming has ended.