An Adventure for Isolation

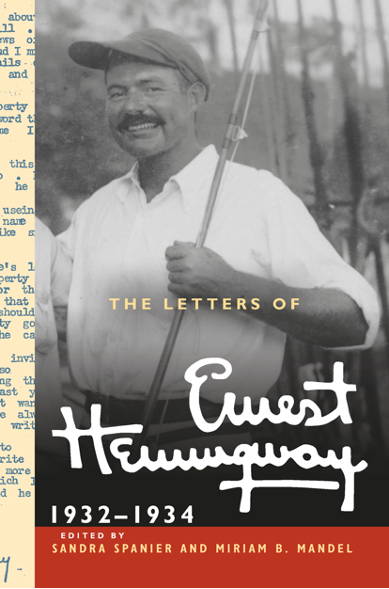

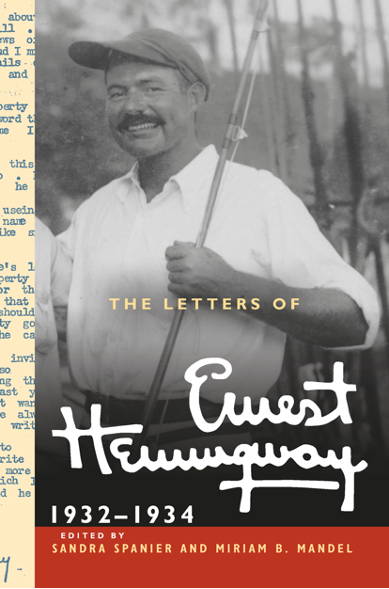

Before COVID-19, readers could cozy up with Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea while hearing the waves on the beach, or imagine Italian streets while reading A Farewell to Arms on business trips and family-visit flights across the world. As people work and read from home during this pandemic, they are gifted with a new Hemingway adventure — Volume 5 of The Letters of Ernest Hemingway, recently published by Cambridge University Press. Just when Hemingway fans need it most, the Hemingway Letters Project presents readers with the most candid, adventurous, and unapologetic version of Hemingway thus far. This volume exhibits his appreciation for the little things in life, a literary legend increasingly aware of his fame, and, as Penn State’s Verna Kale, Associate Editor of the Hemingway Letters Project, puts it in her best Hemingway-speak, “So. Many. Fish.” As people everywhere are able to read Volume 5 from nowhere other than their couches, Hemingway’s letters take readers on a COVID-friendly vacation.

Hemingway always had a way of transporting readers with a certain ease and appreciation for details. Scholars talk about Hemingway’s ability to paint a picture for readers and cite his inspiration from movies, describing his narrative style as “cinematic” (Miriam Mandel liii). His letters are no different, especially in Volume 5. In this volume, Hemingway writes a letter to lexicographer and publisher Wilfred J. Funk containing a list of his favorite words in the English dictionary: “warm, cold, Wood, Food, wine, Morning, Evening, Night, Bed, wife, Sleep” (Mandel, lvii). Reflecting on Hemingway’s list, Penn State’s Sandra Spanier, General Editor of the Hemingway Letters Project, notes, “He is famous for his cynicism, pessimism, and understated irony, but this list shows sensitivity and appreciation of simple pleasures.” Spanier recalls Hemingway’s acute attention to the mundane in the description of potato salad in A Moveable Feast, as well as how amidst fleeing the Italian Army in A Farewell to Arms, the characters joke about the “wonderful rolls and butter and jam they’ll have for breakfast.” As a curator of the little things in life, Hemingway sets himself apart as a meticulous master of the senses and human experience. Shining through in his novels, but even more so in his letters, Hemingway’s awareness and language illustrate how cognizant he was during the period of his life that readers catch a glimpse of in Volume 5.

Similar to how Hemingway relished in good food, drink, and adventure, he also felt one of life’s greatest pleasures was cultivating close relationships. The letters provide readers an inside look into one of Hemingway's most intimate confidants and the volume's most frequent correspondent, Max Perkins. Though Perkins was Hemingway’s editor for a large part of his career, this volume presents his transition from editor, to editor and close friend. Co-editor with Spanier of Volume 5, Miriam Mandel of Tel Aviv University suggests the relationship between Hemingway and Perkins was one of respect, trust, and affection. She explains that in their letters, even while discussing publishing and commentary on Hemingway’s work, a genuine care for each other’s well-being shines through. With a personal relationship with Perkins and a whole lot of fame, Hemingway’s self-assured convictions become more prevalent in these letters. And yet Hemingway was stubborn and protective when it came to his writing and notoriously rejected edits. Spanier stresses that Perkins “recognized and nurtured his talent early on and became a trusted guide [...], but he did very little actual editing of Hemingway’s work.” The only things Perkins edited were words that would subject Hemingway’s writing to censorship issues. As Hemingway becomes increasingly aware of his literary powers, readers can look to the relationship between Hemingway and Perkins as a starting point for some of the most personal and assertive correspondence in the volume.

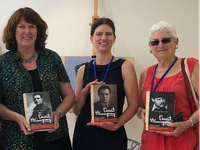

- Sandra Spanier, Verna Kale, and Miriam Mandel at Biennial International Hemingway Conference, Paris. July 2018.

Though Hemingway famously detested his own letters and frequently would add marginal scribbles about how horrible his writing and spelling were, the letters provide lucid portrayals of his inner thoughts. Hemingway had no intention or desire to ever have his letters published. With their publication, Hemingway unknowingly reveals to readers an unedited and untailored version of himself. Contrasting with the author version of Hemingway who wrote the ending of A Farewell to Arms thirty-nine times, the personal version of Hemingway writes impulsively, “I will be damned if I have any vicar pruning my books to please the circulating libraries.” Without the ability to consult Hemingway himself, Spanier reports she and her colleagues wish to give readers the experience of reading the letters “in the same way his intended readers would have experienced them--messy, spontaneous, candid, [and] imperfect.” Though Hemingway’s infamously faulty typewriter cannot be replicated in print, the editors insist on preserving not only the reading experience but also the authenticity of Hemingway, who wrote letters while drunk, energized, during spells of depression, on trips, with nothing else to do besides patiently craft wordplay for friends, and everything in between.

The liveliness of this volume does not stop or start with Hemingway’s quips and ad-libs. Readers are introduced to Hemingway’s hobbies and adventures as he details his experiences during one of his most creative periods. What the letters reveal is that Hemingway was at home in Key West, Florida for only a short period during the two-year time span covered by the volume (1932-1934). Traveling between his hunting trips in Wyoming, Montana, and Arkansas, vacations in Spain, and embarking on fishing expeditions, Hemingway lets go of his perfectionism and writes more spontaneously and freely about his adventures, thoughts, and feelings. Volume 5 also establishes to readers the inspiration behind one of Hemingway’s most famous novels, The Old Man and the Sea. Hemingway spends a lot of this volume detailing the work he does with scientists from the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia and how he learns to fish from Florida fishermen. Letters centered on his passions and travels are important to contextualizing Hemingway’s personality outside of his identity as a writer. As Kale remarks, “There are some folks out there who think Hemingway was just a braggart or a poser, but this volume clearly shows that when he cared about something he immersed himself in it.” His fishing interests took him on trips to Cuba and the Gulf Stream, and even caused him to consider postponing other adventures, such as an African safari he had planned for years, just so he could keep fishing!

- Hemingway and his son, Bumby, with Bumby’s first marlin. Havana Harbor, Summer 1933.

The time of adventure and personal transformation in Hemingway’s life takes place during a period of cultural and political transformation as well. The real-time correspondence of these events provides a clear window into the 1930s. During these years, Hemingway received heavy criticism for the lack of political and social commentary in his work, especially in Death in the Afternoon and Green Hills of Africa (published in 1932 and 1935 respectively). As a result, rebranding Hemingway’s image is a focus of some of the letters and seems to be important to his contemporaries, editors, and readers. However, other letters demonstrate that Hemingway is, in fact, deeply invested in the politics of his time, even if that investment is not explicitly treated in his published work. Such letters include Hemingway’s thoughts on the New Deal, government-funded projects in Florida, strikes, and political unrest in Cuba. As Graduate Research Assistant Katie Warczak remarks, “Far from an isolated writer, Hemingway was abundantly aware of the period of political upheaval through which he was living.” Kale notes this period was influential to the way he continued to write later on, affecting how "he thought about writing in theory and practice.”

The candid communication readers see in this volume provides valuable context to Hemingway’s charms, shortcomings, and talent, as well as the political and cultural world he lived in. From the minute details to the intimate relationship with Perkins and a deep-dive into Hemingway’s love for fishing, this volume leaves readers with something fresh and memorable. Reflecting on her editing process, Warczak shares, “Reading about these locations when traveling isn’t possible for me has been nice because I’ve been able to live somewhat vicariously through these movements while the pandemic restricts my own mobility.” Each letter lays bare Hemingway's personality, sense of adventure, and honesty while we are feeling disconnected, stuck, and craving relatable portrayals of life amidst an isolating pandemic. Years after his heyday, and thanks to the hard work of Spanier, Kale, Mandel, Warczak, and their colleagues at The Hemingway Letters Project, Hemingway still manages to give readers a new sense of adventure exactly when they need it most.

- Katie Warczak at Finca Vigía, Hemingway’s home in Cuba. June 2019.

Before COVID-19, readers could cozy up with Ernest Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea while hearing the waves on the beach, or imagine Italian streets while reading A Farewell to Arms on business trips and family-visit flights across the world. As people work and read from home during this pandemic, they are gifted with a new Hemingway adventure — Volume 5 of The Letters of Ernest Hemingway, recently published by Cambridge University Press. Just when Hemingway fans need it most, the Hemingway Letters Project presents readers with the most candid, adventurous, and unapologetic version of Hemingway thus far. This volume exhibits his appreciation for the little things in life, a literary legend increasingly aware of his fame, and, as Penn State’s Verna Kale, Associate Editor of the Hemingway Letters Project, puts it in her best Hemingway-speak, “So. Many. Fish.” As people everywhere are able to read Volume 5 from nowhere other than their couches, Hemingway’s letters take readers on a COVID-friendly vacation.

Hemingway always had a way of transporting readers with a certain ease and appreciation for details. Scholars talk about Hemingway’s ability to paint a picture for readers and cite his inspiration from movies, describing his narrative style as “cinematic” (Miriam Mandel liii). His letters are no different, especially in Volume 5. In this volume, Hemingway writes a letter to lexicographer and publisher Wilfred J. Funk containing a list of his favorite words in the English dictionary: “warm, cold, Wood, Food, wine, Morning, Evening, Night, Bed, wife, Sleep” (Mandel, lvii). Reflecting on Hemingway’s list, Penn State’s Sandra Spanier, General Editor of the Hemingway Letters Project, notes, “He is famous for his cynicism, pessimism, and understated irony, but this list shows sensitivity and appreciation of simple pleasures.” Spanier recalls Hemingway’s acute attention to the mundane in the description of potato salad in A Moveable Feast, as well as how amidst fleeing the Italian Army in A Farewell to Arms, the characters joke about the “wonderful rolls and butter and jam they’ll have for breakfast.” As a curator of the little things in life, Hemingway sets himself apart as a meticulous master of the senses and human experience. Shining through in his novels, but even more so in his letters, Hemingway’s awareness and language illustrate how cognizant he was during the period of his life that readers catch a glimpse of in Volume 5.

Similar to how Hemingway relished in good food, drink, and adventure, he also felt one of life’s greatest pleasures was cultivating close relationships. The letters provide readers an inside look into one of Hemingway's most intimate confidants and the volume's most frequent correspondent, Max Perkins. Though Perkins was Hemingway’s editor for a large part of his career, this volume presents his transition from editor, to editor and close friend. Co-editor with Spanier of Volume 5, Miriam Mandel of Tel Aviv University suggests the relationship between Hemingway and Perkins was one of respect, trust, and affection. She explains that in their letters, even while discussing publishing and commentary on Hemingway’s work, a genuine care for each other’s well-being shines through. With a personal relationship with Perkins and a whole lot of fame, Hemingway’s self-assured convictions become more prevalent in these letters. And yet Hemingway was stubborn and protective when it came to his writing and notoriously rejected edits. Spanier stresses that Perkins “recognized and nurtured his talent early on and became a trusted guide [...], but he did very little actual editing of Hemingway’s work.” The only things Perkins edited were words that would subject Hemingway’s writing to censorship issues. As Hemingway becomes increasingly aware of his literary powers, readers can look to the relationship between Hemingway and Perkins as a starting point for some of the most personal and assertive correspondence in the volume.

- Sandra Spanier, Verna Kale, and Miriam Mandel at Biennial International Hemingway Conference, Paris. July 2018.

Though Hemingway famously detested his own letters and frequently would add marginal scribbles about how horrible his writing and spelling were, the letters provide lucid portrayals of his inner thoughts. Hemingway had no intention or desire to ever have his letters published. With their publication, Hemingway unknowingly reveals to readers an unedited and untailored version of himself. Contrasting with the author version of Hemingway who wrote the ending of A Farewell to Arms thirty-nine times, the personal version of Hemingway writes impulsively, “I will be damned if I have any vicar pruning my books to please the circulating libraries.” Without the ability to consult Hemingway himself, Spanier reports she and her colleagues wish to give readers the experience of reading the letters “in the same way his intended readers would have experienced them--messy, spontaneous, candid, [and] imperfect.” Though Hemingway’s infamously faulty typewriter cannot be replicated in print, the editors insist on preserving not only the reading experience but also the authenticity of Hemingway, who wrote letters while drunk, energized, during spells of depression, on trips, with nothing else to do besides patiently craft wordplay for friends, and everything in between.

The liveliness of this volume does not stop or start with Hemingway’s quips and ad-libs. Readers are introduced to Hemingway’s hobbies and adventures as he details his experiences during one of his most creative periods. What the letters reveal is that Hemingway was at home in Key West, Florida for only a short period during the two-year time span covered by the volume (1932-1934). Traveling between his hunting trips in Wyoming, Montana, and Arkansas, vacations in Spain, and embarking on fishing expeditions, Hemingway lets go of his perfectionism and writes more spontaneously and freely about his adventures, thoughts, and feelings. Volume 5 also establishes to readers the inspiration behind one of Hemingway’s most famous novels, The Old Man and the Sea. Hemingway spends a lot of this volume detailing the work he does with scientists from the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia and how he learns to fish from Florida fishermen. Letters centered on his passions and travels are important to contextualizing Hemingway’s personality outside of his identity as a writer. As Kale remarks, “There are some folks out there who think Hemingway was just a braggart or a poser, but this volume clearly shows that when he cared about something he immersed himself in it.” His fishing interests took him on trips to Cuba and the Gulf Stream, and even caused him to consider postponing other adventures, such as an African safari he had planned for years, just so he could keep fishing!

- Hemingway and his son, Bumby, with Bumby’s first marlin. Havana Harbor, Summer 1933.

The time of adventure and personal transformation in Hemingway’s life takes place during a period of cultural and political transformation as well. The real-time correspondence of these events provides a clear window into the 1930s. During these years, Hemingway received heavy criticism for the lack of political and social commentary in his work, especially in Death in the Afternoon and Green Hills of Africa (published in 1932 and 1935 respectively). As a result, rebranding Hemingway’s image is a focus of some of the letters and seems to be important to his contemporaries, editors, and readers. However, other letters demonstrate that Hemingway is, in fact, deeply invested in the politics of his time, even if that investment is not explicitly treated in his published work. Such letters include Hemingway’s thoughts on the New Deal, government-funded projects in Florida, strikes, and political unrest in Cuba. As Graduate Research Assistant Katie Warczak remarks, “Far from an isolated writer, Hemingway was abundantly aware of the period of political upheaval through which he was living.” Kale notes this period was influential to the way he continued to write later on, affecting how "he thought about writing in theory and practice.”

The candid communication readers see in this volume provides valuable context to Hemingway’s charms, shortcomings, and talent, as well as the political and cultural world he lived in. From the minute details to the intimate relationship with Perkins and a deep-dive into Hemingway’s love for fishing, this volume leaves readers with something fresh and memorable. Reflecting on her editing process, Warczak shares, “Reading about these locations when traveling isn’t possible for me has been nice because I’ve been able to live somewhat vicariously through these movements while the pandemic restricts my own mobility.” Each letter lays bare Hemingway's personality, sense of adventure, and honesty while we are feeling disconnected, stuck, and craving relatable portrayals of life amidst an isolating pandemic. Years after his heyday, and thanks to the hard work of Spanier, Kale, Mandel, Warczak, and their colleagues at The Hemingway Letters Project, Hemingway still manages to give readers a new sense of adventure exactly when they need it most.

- Katie Warczak at Finca Vigía, Hemingway’s home in Cuba. June 2019.