Ghosts of the Archives

A fluorescent light flickers with a buzz as I run my fingers along the spines of the PS stacks in the Pattee library searching for the call number I’ve written on the back of a crumpled receipt. It’s 11:35 PM and I may be the only student in the American literature section, but it’s clear that I’m not alone. The library’s literal ghosts are well known. Fred Lewis Pattee’s name adorns the building while his spectre looms over the study of American Literature at Penn State. Tour guides whisper in hushed voices about Betsy Aardsma, the English graduate student whose unsolved murder in 1969 took place in the stacks. The library’s literary ghosts, however, haunt the archives more quietly. CALS at Penn State represents a wide range of faculty and student literary interests, interests that probe the edges of what we can even call American literature. Each year, the Center offers Americanist graduate students grants to travel to research collections across the United States. The Special Collections at Penn State, however, house their own ambitious range of material.

The American Author Collections boast sought-after materials from James Fenimore Cooper, Emily Dickinson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, Henry David Thoreau, and Walt Whitman. Some collections, like the Charles L. Blockson collection of African-Americana and the African Diaspora, are honored with their own rooms. The Blockson contains a stunning spread of books, artifacts, and art, some of which are attributed to figures like Josephine Baker and Paul Robeson. Others, like the Arthur O. Lewis Utopia collection, have qualified Penn State to host events like the 2011 Society for Utopian Studies Conference. While these collections have enjoyed some degree of notoriety, others silently haunt the crevices of the Special Collections unnoticed.

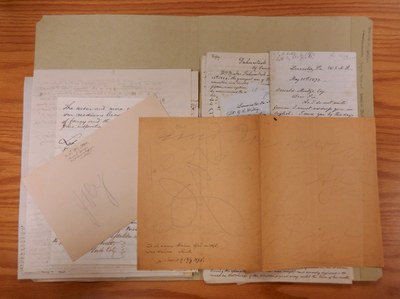

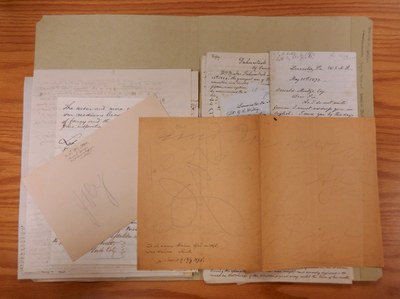

One of the strangest collection of spirits hides in the Rare Books room of Paterno Library. The Occult collection is made up of handbooks of mesmerists, memoirs of mediums, and letters from notable nineteenth-century Spiritualist Andrew Jackson Davis. One box of ephemera contains scraps of automatic writing amongst the letters, a practice performed by nineteenth-century mediums who wrote at the direction of spirits. The image to the left is a piece of such writing, with the name “Joey” seeming to appear twice during the séance (Figure 1). I’ve twice now visited these papers and twice found new shapes and meanings in the automatic writing; the archive yields new interpretations on every visit. The example to the right is from a photo album of spirit

One of the strangest collection of spirits hides in the Rare Books room of Paterno Library. The Occult collection is made up of handbooks of mesmerists, memoirs of mediums, and letters from notable nineteenth-century Spiritualist Andrew Jackson Davis. One box of ephemera contains scraps of automatic writing amongst the letters, a practice performed by nineteenth-century mediums who wrote at the direction of spirits. The image to the left is a piece of such writing, with the name “Joey” seeming to appear twice during the séance (Figure 1). I’ve twice now visited these papers and twice found new shapes and meanings in the automatic writing; the archive yields new interpretations on every visit. The example to the right is from a photo album of spirit  photography, where spirits of the departed hover above the seated portrait subject (Figure 2) – a practice even endorsed by Mary Todd Lincoln, whose departed husband appeared to her in a spirit photo. While the authors, photographers, and mourners are gone to us now, they speak through the artifacts they’ve left behind to tell us how they themselves viewed the permeable boundary between life and death.

photography, where spirits of the departed hover above the seated portrait subject (Figure 2) – a practice even endorsed by Mary Todd Lincoln, whose departed husband appeared to her in a spirit photo. While the authors, photographers, and mourners are gone to us now, they speak through the artifacts they’ve left behind to tell us how they themselves viewed the permeable boundary between life and death.

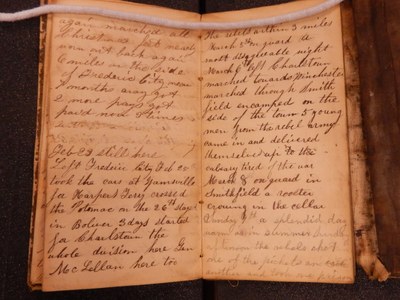

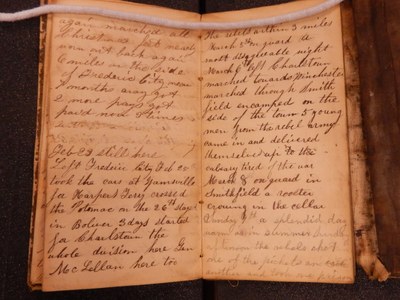

Another collection of voices from beyond the grave is the library’s collection of Civil War Diaries. Morris W. Hackman’s diary [pictured right] illustrates the daily life of a Union soldier as he marched on Christmas day until his feet were sore, continued through Harper’s Ferry, saw devastation on the battlefield, and was captured by "rebel soldiers" (Figure 3). Similarly, the Emilie Davis Diaries preserve the voice of a free Philadelphian African American woman who lived during the Civil War. Davis’s diaries span a few years of her early womanhood during which she witnessed the aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg and Abraham Lincoln’s funeral. This particular collection is on loan to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania at the moment. Another small collection from this era lists the 30,000 non-reporting drafted men and deserters from the Union army between 1861 and 1865. One can learn facts about the Civil War through a documentary or history book, but to hold these diaries and reports is to truly hear history. Listening to Emilie Davis’s authorial voice after reading the diary of a soldier and considering the institutional records allows one to understand the ways this moment in history was lived.

Another collection of voices from beyond the grave is the library’s collection of Civil War Diaries. Morris W. Hackman’s diary [pictured right] illustrates the daily life of a Union soldier as he marched on Christmas day until his feet were sore, continued through Harper’s Ferry, saw devastation on the battlefield, and was captured by "rebel soldiers" (Figure 3). Similarly, the Emilie Davis Diaries preserve the voice of a free Philadelphian African American woman who lived during the Civil War. Davis’s diaries span a few years of her early womanhood during which she witnessed the aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg and Abraham Lincoln’s funeral. This particular collection is on loan to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania at the moment. Another small collection from this era lists the 30,000 non-reporting drafted men and deserters from the Union army between 1861 and 1865. One can learn facts about the Civil War through a documentary or history book, but to hold these diaries and reports is to truly hear history. Listening to Emilie Davis’s authorial voice after reading the diary of a soldier and considering the institutional records allows one to understand the ways this moment in history was lived.

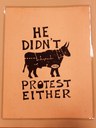

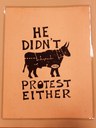

Voices from the political movements of the 1960s and 1970s speak loudly in the special collections. The Thomas W. Benson Political Protest Collection houses visual art from student activist movements. Two notable examples from a workshop at UC Berkeley can be seen here (Figures 4 and 5). The striking visual rhetoric of this collection collapses the distance between our contemporary campus movements and the anti-war protests fifty years ago. Representing the same era, the Jack Rabin Collection on Alabama Civil Rights and Southern Activists hosts materials from the Selma-to-Montgomery march and other demonstrations

Voices from the political movements of the 1960s and 1970s speak loudly in the special collections. The Thomas W. Benson Political Protest Collection houses visual art from student activist movements. Two notable examples from a workshop at UC Berkeley can be seen here (Figures 4 and 5). The striking visual rhetoric of this collection collapses the distance between our contemporary campus movements and the anti-war protests fifty years ago. Representing the same era, the Jack Rabin Collection on Alabama Civil Rights and Southern Activists hosts materials from the Selma-to-Montgomery march and other demonstrations and sit-ins. Be they students or Civil Rights leaders, the voices of this era speak boldly to anyone who listens.

and sit-ins. Be they students or Civil Rights leaders, the voices of this era speak boldly to anyone who listens.

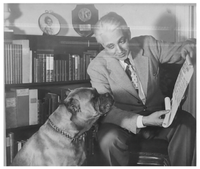

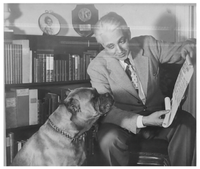

Penn State is home to the Fred Lewis Pattees of American Literature, but also to the personal writing and ephemera of names unknown beyond their personal circles. These ghosts wait in the archives to tell us their stories; we need only take the time to listen. While we may think of the library’s ghosts as victims of untimely deaths or witnesses of wartime atrocities, there are also stories to enchant us as we sift through books and boxes. In the PSU Altoona archive lives the story of an enormous canine named Thor, a local celebrity in his time (pictured right) (Figure 6). Thor served in World War II as part of the “Dogs for Defense” initiative. He returned to fanfare and infamy; his archive contains his photograph, a brief biography, and his well-deserved Key to the City of Altoona. While he may not have been able to tell us his story in person, holding Thor’s archive collapses time in a way that a history textbook never could. To hold the most intimate diary of a soldier is to listen closely to the quiet joys, subtle heartbreaks, and careful secrets of American history and literature that only archival spirits can tell us.

us their stories; we need only take the time to listen. While we may think of the library’s ghosts as victims of untimely deaths or witnesses of wartime atrocities, there are also stories to enchant us as we sift through books and boxes. In the PSU Altoona archive lives the story of an enormous canine named Thor, a local celebrity in his time (pictured right) (Figure 6). Thor served in World War II as part of the “Dogs for Defense” initiative. He returned to fanfare and infamy; his archive contains his photograph, a brief biography, and his well-deserved Key to the City of Altoona. While he may not have been able to tell us his story in person, holding Thor’s archive collapses time in a way that a history textbook never could. To hold the most intimate diary of a soldier is to listen closely to the quiet joys, subtle heartbreaks, and careful secrets of American history and literature that only archival spirits can tell us.

***Liana Kathleen Glew is the 2017-2018 CALS Graduate Research Assistant. She wishes to thank Clara Drummond and the Special Collections archivists for their knowledge and assistance.

Title Photo: "Front of Pattee Library." Physical Plant, 1965. Penn State University Archives, Special Collections Library, University Libraries, Pennsylvania State University.

Figure 1: "19th Century German Spiritualism Collection: Correspondence." Andrew Jackson Davis 1894, 2281. Penn State University Archives, Special Collections Library, University Libraries, Pennsylvania State University.

Figure 2: "19th Century German Spiritualism Collection: Photo Album." Andrew Jackson Davis 1894, 2281. Penn State University Archives, Special Collections Library, University Libraries, Pennsylvania State University.

Figure 3: "Morris W. Hackman Civil War Diary." 1862-1863, 2075, HCVF 7. Penn State University Archives, Special Collections Library, University Libraries, Pennsylvania State University.

Figure 4: "He Didn't Protest Either." Thomas W. Benson Papers, Political Protest Posters, 1960s-70s, 6352. Penn State University Archives, Special Collections Library, University Libraries, Pennsylvania State University.

Figure 5: "Peace Now." Thomas W. Benson Papers, Political Protest Posters, 1960s-70s, 6352. Penn State University Archives, Special Collections Library, University Libraries, Pennsylvania State University.

Figure 6: "Eiche and Thor." Eiche Collection, 1950. Robert E. Eiche Library exhibit, Penn State Altoona, University Libraries, Pennsylvania State University.

A fluorescent light flickers with a buzz as I run my fingers along the spines of the PS stacks in the Pattee library searching for the call number I’ve written on the back of a crumpled receipt. It’s 11:35 PM and I may be the only student in the American literature section, but it’s clear that I’m not alone. The library’s literal ghosts are well known. Fred Lewis Pattee’s name adorns the building while his spectre looms over the study of American Literature at Penn State. Tour guides whisper in hushed voices about Betsy Aardsma, the English graduate student whose unsolved murder in 1969 took place in the stacks. The library’s literary ghosts, however, haunt the archives more quietly. CALS at Penn State represents a wide range of faculty and student literary interests, interests that probe the edges of what we can even call American literature. Each year, the Center offers Americanist graduate students grants to travel to research collections across the United States. The Special Collections at Penn State, however, house their own ambitious range of material.

The American Author Collections boast sought-after materials from James Fenimore Cooper, Emily Dickinson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Herman Melville, Henry David Thoreau, and Walt Whitman. Some collections, like the Charles L. Blockson collection of African-Americana and the African Diaspora, are honored with their own rooms. The Blockson contains a stunning spread of books, artifacts, and art, some of which are attributed to figures like Josephine Baker and Paul Robeson. Others, like the Arthur O. Lewis Utopia collection, have qualified Penn State to host events like the 2011 Society for Utopian Studies Conference. While these collections have enjoyed some degree of notoriety, others silently haunt the crevices of the Special Collections unnoticed.

One of the strangest collection of spirits hides in the Rare Books room of Paterno Library. The Occult collection is made up of handbooks of mesmerists, memoirs of mediums, and letters from notable nineteenth-century Spiritualist Andrew Jackson Davis. One box of ephemera contains scraps of automatic writing amongst the letters, a practice performed by nineteenth-century mediums who wrote at the direction of spirits. The image to the left is a piece of such writing, with the name “Joey” seeming to appear twice during the séance (Figure 1). I’ve twice now visited these papers and twice found new shapes and meanings in the automatic writing; the archive yields new interpretations on every visit. The example to the right is from a photo album of spirit

One of the strangest collection of spirits hides in the Rare Books room of Paterno Library. The Occult collection is made up of handbooks of mesmerists, memoirs of mediums, and letters from notable nineteenth-century Spiritualist Andrew Jackson Davis. One box of ephemera contains scraps of automatic writing amongst the letters, a practice performed by nineteenth-century mediums who wrote at the direction of spirits. The image to the left is a piece of such writing, with the name “Joey” seeming to appear twice during the séance (Figure 1). I’ve twice now visited these papers and twice found new shapes and meanings in the automatic writing; the archive yields new interpretations on every visit. The example to the right is from a photo album of spirit  photography, where spirits of the departed hover above the seated portrait subject (Figure 2) – a practice even endorsed by Mary Todd Lincoln, whose departed husband appeared to her in a spirit photo. While the authors, photographers, and mourners are gone to us now, they speak through the artifacts they’ve left behind to tell us how they themselves viewed the permeable boundary between life and death.

photography, where spirits of the departed hover above the seated portrait subject (Figure 2) – a practice even endorsed by Mary Todd Lincoln, whose departed husband appeared to her in a spirit photo. While the authors, photographers, and mourners are gone to us now, they speak through the artifacts they’ve left behind to tell us how they themselves viewed the permeable boundary between life and death.

Another collection of voices from beyond the grave is the library’s collection of Civil War Diaries. Morris W. Hackman’s diary [pictured right] illustrates the daily life of a Union soldier as he marched on Christmas day until his feet were sore, continued through Harper’s Ferry, saw devastation on the battlefield, and was captured by "rebel soldiers" (Figure 3). Similarly, the Emilie Davis Diaries preserve the voice of a free Philadelphian African American woman who lived during the Civil War. Davis’s diaries span a few years of her early womanhood during which she witnessed the aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg and Abraham Lincoln’s funeral. This particular collection is on loan to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania at the moment. Another small collection from this era lists the 30,000 non-reporting drafted men and deserters from the Union army between 1861 and 1865. One can learn facts about the Civil War through a documentary or history book, but to hold these diaries and reports is to truly hear history. Listening to Emilie Davis’s authorial voice after reading the diary of a soldier and considering the institutional records allows one to understand the ways this moment in history was lived.

Another collection of voices from beyond the grave is the library’s collection of Civil War Diaries. Morris W. Hackman’s diary [pictured right] illustrates the daily life of a Union soldier as he marched on Christmas day until his feet were sore, continued through Harper’s Ferry, saw devastation on the battlefield, and was captured by "rebel soldiers" (Figure 3). Similarly, the Emilie Davis Diaries preserve the voice of a free Philadelphian African American woman who lived during the Civil War. Davis’s diaries span a few years of her early womanhood during which she witnessed the aftermath of the Battle of Gettysburg and Abraham Lincoln’s funeral. This particular collection is on loan to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania at the moment. Another small collection from this era lists the 30,000 non-reporting drafted men and deserters from the Union army between 1861 and 1865. One can learn facts about the Civil War through a documentary or history book, but to hold these diaries and reports is to truly hear history. Listening to Emilie Davis’s authorial voice after reading the diary of a soldier and considering the institutional records allows one to understand the ways this moment in history was lived.

Voices from the political movements of the 1960s and 1970s speak loudly in the special collections. The Thomas W. Benson Political Protest Collection houses visual art from student activist movements. Two notable examples from a workshop at UC Berkeley can be seen here (Figures 4 and 5). The striking visual rhetoric of this collection collapses the distance between our contemporary campus movements and the anti-war protests fifty years ago. Representing the same era, the Jack Rabin Collection on Alabama Civil Rights and Southern Activists hosts materials from the Selma-to-Montgomery march and other demonstrations

Voices from the political movements of the 1960s and 1970s speak loudly in the special collections. The Thomas W. Benson Political Protest Collection houses visual art from student activist movements. Two notable examples from a workshop at UC Berkeley can be seen here (Figures 4 and 5). The striking visual rhetoric of this collection collapses the distance between our contemporary campus movements and the anti-war protests fifty years ago. Representing the same era, the Jack Rabin Collection on Alabama Civil Rights and Southern Activists hosts materials from the Selma-to-Montgomery march and other demonstrations and sit-ins. Be they students or Civil Rights leaders, the voices of this era speak boldly to anyone who listens.

and sit-ins. Be they students or Civil Rights leaders, the voices of this era speak boldly to anyone who listens.

Penn State is home to the Fred Lewis Pattees of American Literature, but also to the personal writing and ephemera of names unknown beyond their personal circles. These ghosts wait in the archives to tell us their stories; we need only take the time to listen. While we may think of the library’s ghosts as victims of untimely deaths or witnesses of wartime atrocities, there are also stories to enchant us as we sift through books and boxes. In the PSU Altoona archive lives the story of an enormous canine named Thor, a local celebrity in his time (pictured right) (Figure 6). Thor served in World War II as part of the “Dogs for Defense” initiative. He returned to fanfare and infamy; his archive contains his photograph, a brief biography, and his well-deserved Key to the City of Altoona. While he may not have been able to tell us his story in person, holding Thor’s archive collapses time in a way that a history textbook never could. To hold the most intimate diary of a soldier is to listen closely to the quiet joys, subtle heartbreaks, and careful secrets of American history and literature that only archival spirits can tell us.

us their stories; we need only take the time to listen. While we may think of the library’s ghosts as victims of untimely deaths or witnesses of wartime atrocities, there are also stories to enchant us as we sift through books and boxes. In the PSU Altoona archive lives the story of an enormous canine named Thor, a local celebrity in his time (pictured right) (Figure 6). Thor served in World War II as part of the “Dogs for Defense” initiative. He returned to fanfare and infamy; his archive contains his photograph, a brief biography, and his well-deserved Key to the City of Altoona. While he may not have been able to tell us his story in person, holding Thor’s archive collapses time in a way that a history textbook never could. To hold the most intimate diary of a soldier is to listen closely to the quiet joys, subtle heartbreaks, and careful secrets of American history and literature that only archival spirits can tell us.

***Liana Kathleen Glew is the 2017-2018 CALS Graduate Research Assistant. She wishes to thank Clara Drummond and the Special Collections archivists for their knowledge and assistance.

Title Photo: "Front of Pattee Library." Physical Plant, 1965. Penn State University Archives, Special Collections Library, University Libraries, Pennsylvania State University.

Figure 1: "19th Century German Spiritualism Collection: Correspondence." Andrew Jackson Davis 1894, 2281. Penn State University Archives, Special Collections Library, University Libraries, Pennsylvania State University.

Figure 2: "19th Century German Spiritualism Collection: Photo Album." Andrew Jackson Davis 1894, 2281. Penn State University Archives, Special Collections Library, University Libraries, Pennsylvania State University.

Figure 3: "Morris W. Hackman Civil War Diary." 1862-1863, 2075, HCVF 7. Penn State University Archives, Special Collections Library, University Libraries, Pennsylvania State University.

Figure 4: "He Didn't Protest Either." Thomas W. Benson Papers, Political Protest Posters, 1960s-70s, 6352. Penn State University Archives, Special Collections Library, University Libraries, Pennsylvania State University.

Figure 5: "Peace Now." Thomas W. Benson Papers, Political Protest Posters, 1960s-70s, 6352. Penn State University Archives, Special Collections Library, University Libraries, Pennsylvania State University.

Figure 6: "Eiche and Thor." Eiche Collection, 1950. Robert E. Eiche Library exhibit, Penn State Altoona, University Libraries, Pennsylvania State University.