Institutionally Speaking: the 2018 CALS Spring Symposium

The past decade of humanities scholarship has trended towards inward-looking reflections on the state of the discipline and outward-looking critiques of the university and other related American institutions. This increasing tendency to turn critique towards institutions has led to areas of scholarship like “Critical University Studies” and “post-critique.” This year’s CALS symposium, Institutionally Speaking: the Object(s) of American Literary and Cultural Criticism, aimed to push through these recent tendencies to consider the wide array of institutions and objects that make up humanities critiques. On Monday, March 18, 2018, the Center for American Literary Studies invited six scholars from around the country to join six Penn State faculty in exploring the possibilities of socially committed criticism that responds to specific institutional crises. Each speaker was asked to choose one object of criticism and one related institution. Over the course of one day and two roundtables, the twelve speakers reflected upon the limits and possibilities of critique, modeling exciting, new ways forward.

The first roundtable covered a range of topics, but spoke to a few common themes like technology and  knowledge-production. Kandice Chuh (The Graduate Center, CUNY) considered the state of the contemporary humanities, following questions provoked by Lan Samantha Chang’s novella “Hunger.” Chuh pointed to the fact that “Critical University Studies” have become institutionalized themselves and asked, in the context of the crisis in the humanities, “just what is it that we’re being asked to defend?” Her provocative question situated the humanities as an object of the nation-state, a tool to promote aesthetic education and liberal values of private property. Brian Lennon (Penn State University) followed Chuh’s presentation with a riveting reflection on passwords in the context of “the University at war.” Lennon situated the password’s genealogy in the intersection between philology and cryptology: a genealogy shared with warfare. Criticism, to Lennon, shares an investment in cryptoanalysis with the technology and war industries.

knowledge-production. Kandice Chuh (The Graduate Center, CUNY) considered the state of the contemporary humanities, following questions provoked by Lan Samantha Chang’s novella “Hunger.” Chuh pointed to the fact that “Critical University Studies” have become institutionalized themselves and asked, in the context of the crisis in the humanities, “just what is it that we’re being asked to defend?” Her provocative question situated the humanities as an object of the nation-state, a tool to promote aesthetic education and liberal values of private property. Brian Lennon (Penn State University) followed Chuh’s presentation with a riveting reflection on passwords in the context of “the University at war.” Lennon situated the password’s genealogy in the intersection between philology and cryptology: a genealogy shared with warfare. Criticism, to Lennon, shares an investment in cryptoanalysis with the technology and war industries.

Elizabeth Anker (Cornell University) brought us to a stunning realization through her reading of Ursula K. Le Guin’s short story, “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas.” Anker read the dystopian story not for the ways that privilege relies on structural violence - as is the common reading of the story - but as a metaphor for criticism. Just as Freud claimed that pleasure relies on pain, Anker claimed that “critique” as an institution relies on (often-self-created) structural violence to operate. John Marsh (Penn State University) performed a reading of Isaac Asimov’s “Liar!” that considered the various iterations of hope - apocalyptic hope, political hope, economic home, individual hope - that overlay our criticism. Marsh invoked Asimov’s robots’ rules of telling humans what they want to hear, asking “what do literary critics want to hear?” and challenging the social commitments of criticism.

that privilege relies on structural violence - as is the common reading of the story - but as a metaphor for criticism. Just as Freud claimed that pleasure relies on pain, Anker claimed that “critique” as an institution relies on (often-self-created) structural violence to operate. John Marsh (Penn State University) performed a reading of Isaac Asimov’s “Liar!” that considered the various iterations of hope - apocalyptic hope, political hope, economic home, individual hope - that overlay our criticism. Marsh invoked Asimov’s robots’ rules of telling humans what they want to hear, asking “what do literary critics want to hear?” and challenging the social commitments of criticism.

Enacting the social commitments of criticism, Louellyn White (Concordia University) spoke both theoretically  and concretely about the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, where native children were brought for cultural extinction and assimilation between 1879 and 1918. White theorized how we tell histories and hear descendent voices, weaving in stories from her grandfather’s time at Carlisle and details of her activist efforts to preserve parts of the institution as heritage centers. Following Professor White’s critical engagement with history, Shirley Moody-Turner (Penn State University) considered African American author, educator and activist Anna Julia Cooper’s scrapbooks in the context of knowledge production and print culture. Moody-Turner asked us what mode of criticism might help us understand why people keep, cut, and archive certain things, combining critique, caretaking, and fact-construction.

and concretely about the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, where native children were brought for cultural extinction and assimilation between 1879 and 1918. White theorized how we tell histories and hear descendent voices, weaving in stories from her grandfather’s time at Carlisle and details of her activist efforts to preserve parts of the institution as heritage centers. Following Professor White’s critical engagement with history, Shirley Moody-Turner (Penn State University) considered African American author, educator and activist Anna Julia Cooper’s scrapbooks in the context of knowledge production and print culture. Moody-Turner asked us what mode of criticism might help us understand why people keep, cut, and archive certain things, combining critique, caretaking, and fact-construction.

The speakers at the second roundtable converged on topics like race, labor, and art. Chris Nealon (Johns Hopkins University) introduced his objects by asking probing questions about Marx and those who don’t have  a direct relation to the labor that produces their objects. Pointing out that “you never leave the theatre humming the critique,” Professor Nealon ceded his time to a song, “Are My Hands Clean?” by Sweet Honey in the Rock, an object that sparked much conversation during the Q&A. Richard Purcell (Carnegie Mellon University) was the only speaker to take a film as his object of critique, focusing on Charlie Ahearn’s 1979 “The Deadly Art of Survival.” Purcell presented the film itself as a critique, pointing to its use of blacksploitation tropes, scenes of leisure time, situation amongst a culture of collectivism, and presentation of singular heroism. Following this practice of amplifying an object’s critique, Amira Rose Davis (Penn State University) looked at black women athletes’ autobiographies. She presented a timeline of African American women in the Olympics and the groups that later used their bodies for commercial and political gains to argue that the US didn’t see black women athletes as threatening political beings during the Civil Rights era and beyond, and thus felt comfortable sending them abroad as international ambassadors.

a direct relation to the labor that produces their objects. Pointing out that “you never leave the theatre humming the critique,” Professor Nealon ceded his time to a song, “Are My Hands Clean?” by Sweet Honey in the Rock, an object that sparked much conversation during the Q&A. Richard Purcell (Carnegie Mellon University) was the only speaker to take a film as his object of critique, focusing on Charlie Ahearn’s 1979 “The Deadly Art of Survival.” Purcell presented the film itself as a critique, pointing to its use of blacksploitation tropes, scenes of leisure time, situation amongst a culture of collectivism, and presentation of singular heroism. Following this practice of amplifying an object’s critique, Amira Rose Davis (Penn State University) looked at black women athletes’ autobiographies. She presented a timeline of African American women in the Olympics and the groups that later used their bodies for commercial and political gains to argue that the US didn’t see black women athletes as threatening political beings during the Civil Rights era and beyond, and thus felt comfortable sending them abroad as international ambassadors.

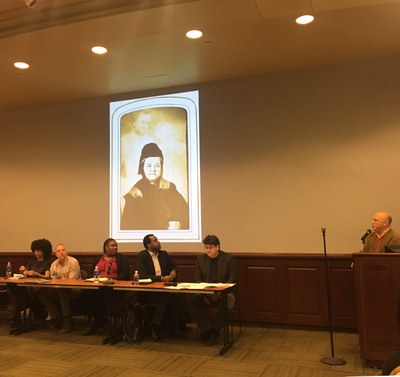

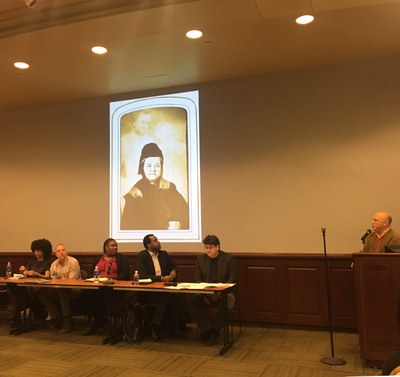

Returning to Chris Nealon’s economic focus, Annie McClanahan (University of California, Irvine) considered  tip/gig work and the dilemma it presents for literary form. A growing type of labor in the US, tip work and gig work encourages more fluidity, experimental temporalities, and fractured relationships in contemporary narratives. Ebony Coletu (Penn State University) followed McClanahan by considering Fannie Lou Hamer’s speech about registering as a voter. Coletu presented voter registration forms as “the battleground for resources and access,” but also as a tool for shrinking black worlds. Chris Castiglia (Penn State University) concluded the roundtable with the provocation to view a critique as an implicit ideal. Castiglia presented William Mumler’s spirit photos and Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s candy sculptures to ask us to think about the roles belief, idealism, grief, and love play in our critique. Perhaps, Castiglia suggested, critics might invest a sense of belief and infinity in our objects.

tip/gig work and the dilemma it presents for literary form. A growing type of labor in the US, tip work and gig work encourages more fluidity, experimental temporalities, and fractured relationships in contemporary narratives. Ebony Coletu (Penn State University) followed McClanahan by considering Fannie Lou Hamer’s speech about registering as a voter. Coletu presented voter registration forms as “the battleground for resources and access,” but also as a tool for shrinking black worlds. Chris Castiglia (Penn State University) concluded the roundtable with the provocation to view a critique as an implicit ideal. Castiglia presented William Mumler’s spirit photos and Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s candy sculptures to ask us to think about the roles belief, idealism, grief, and love play in our critique. Perhaps, Castiglia suggested, critics might invest a sense of belief and infinity in our objects.

The day finished with a panel of graduate student symposium organizers who asked probing questions about  communities, activism, and the University. The following discussion remarked upon the ways the day’s events engaged with - and went beyond - the now-institutionalized practice of post-critique. And indeed they did. Unlike many other conversations in the recent past, Institutionally Speaking did not get hung up on debates about the crisis in the humanities or critique vs. post-critique. Participants presented stirring, challenging objects that helped to unsettle our notions of what the job of the critic is or should be. Critique means amplifying our objects, reconsidering our perceptions of knowledge-production, actively reforming and challenging our institutions, and finding the ideals buried within our engagements with art, literature, music, and technology.

communities, activism, and the University. The following discussion remarked upon the ways the day’s events engaged with - and went beyond - the now-institutionalized practice of post-critique. And indeed they did. Unlike many other conversations in the recent past, Institutionally Speaking did not get hung up on debates about the crisis in the humanities or critique vs. post-critique. Participants presented stirring, challenging objects that helped to unsettle our notions of what the job of the critic is or should be. Critique means amplifying our objects, reconsidering our perceptions of knowledge-production, actively reforming and challenging our institutions, and finding the ideals buried within our engagements with art, literature, music, and technology.

The past decade of humanities scholarship has trended towards inward-looking reflections on the state of the discipline and outward-looking critiques of the university and other related American institutions. This increasing tendency to turn critique towards institutions has led to areas of scholarship like “Critical University Studies” and “post-critique.” This year’s CALS symposium, Institutionally Speaking: the Object(s) of American Literary and Cultural Criticism, aimed to push through these recent tendencies to consider the wide array of institutions and objects that make up humanities critiques. On Monday, March 18, 2018, the Center for American Literary Studies invited six scholars from around the country to join six Penn State faculty in exploring the possibilities of socially committed criticism that responds to specific institutional crises. Each speaker was asked to choose one object of criticism and one related institution. Over the course of one day and two roundtables, the twelve speakers reflected upon the limits and possibilities of critique, modeling exciting, new ways forward.

The first roundtable covered a range of topics, but spoke to a few common themes like technology and  knowledge-production. Kandice Chuh (The Graduate Center, CUNY) considered the state of the contemporary humanities, following questions provoked by Lan Samantha Chang’s novella “Hunger.” Chuh pointed to the fact that “Critical University Studies” have become institutionalized themselves and asked, in the context of the crisis in the humanities, “just what is it that we’re being asked to defend?” Her provocative question situated the humanities as an object of the nation-state, a tool to promote aesthetic education and liberal values of private property. Brian Lennon (Penn State University) followed Chuh’s presentation with a riveting reflection on passwords in the context of “the University at war.” Lennon situated the password’s genealogy in the intersection between philology and cryptology: a genealogy shared with warfare. Criticism, to Lennon, shares an investment in cryptoanalysis with the technology and war industries.

knowledge-production. Kandice Chuh (The Graduate Center, CUNY) considered the state of the contemporary humanities, following questions provoked by Lan Samantha Chang’s novella “Hunger.” Chuh pointed to the fact that “Critical University Studies” have become institutionalized themselves and asked, in the context of the crisis in the humanities, “just what is it that we’re being asked to defend?” Her provocative question situated the humanities as an object of the nation-state, a tool to promote aesthetic education and liberal values of private property. Brian Lennon (Penn State University) followed Chuh’s presentation with a riveting reflection on passwords in the context of “the University at war.” Lennon situated the password’s genealogy in the intersection between philology and cryptology: a genealogy shared with warfare. Criticism, to Lennon, shares an investment in cryptoanalysis with the technology and war industries.

Elizabeth Anker (Cornell University) brought us to a stunning realization through her reading of Ursula K. Le Guin’s short story, “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas.” Anker read the dystopian story not for the ways that privilege relies on structural violence - as is the common reading of the story - but as a metaphor for criticism. Just as Freud claimed that pleasure relies on pain, Anker claimed that “critique” as an institution relies on (often-self-created) structural violence to operate. John Marsh (Penn State University) performed a reading of Isaac Asimov’s “Liar!” that considered the various iterations of hope - apocalyptic hope, political hope, economic home, individual hope - that overlay our criticism. Marsh invoked Asimov’s robots’ rules of telling humans what they want to hear, asking “what do literary critics want to hear?” and challenging the social commitments of criticism.

that privilege relies on structural violence - as is the common reading of the story - but as a metaphor for criticism. Just as Freud claimed that pleasure relies on pain, Anker claimed that “critique” as an institution relies on (often-self-created) structural violence to operate. John Marsh (Penn State University) performed a reading of Isaac Asimov’s “Liar!” that considered the various iterations of hope - apocalyptic hope, political hope, economic home, individual hope - that overlay our criticism. Marsh invoked Asimov’s robots’ rules of telling humans what they want to hear, asking “what do literary critics want to hear?” and challenging the social commitments of criticism.

Enacting the social commitments of criticism, Louellyn White (Concordia University) spoke both theoretically  and concretely about the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, where native children were brought for cultural extinction and assimilation between 1879 and 1918. White theorized how we tell histories and hear descendent voices, weaving in stories from her grandfather’s time at Carlisle and details of her activist efforts to preserve parts of the institution as heritage centers. Following Professor White’s critical engagement with history, Shirley Moody-Turner (Penn State University) considered African American author, educator and activist Anna Julia Cooper’s scrapbooks in the context of knowledge production and print culture. Moody-Turner asked us what mode of criticism might help us understand why people keep, cut, and archive certain things, combining critique, caretaking, and fact-construction.

and concretely about the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, where native children were brought for cultural extinction and assimilation between 1879 and 1918. White theorized how we tell histories and hear descendent voices, weaving in stories from her grandfather’s time at Carlisle and details of her activist efforts to preserve parts of the institution as heritage centers. Following Professor White’s critical engagement with history, Shirley Moody-Turner (Penn State University) considered African American author, educator and activist Anna Julia Cooper’s scrapbooks in the context of knowledge production and print culture. Moody-Turner asked us what mode of criticism might help us understand why people keep, cut, and archive certain things, combining critique, caretaking, and fact-construction.

The speakers at the second roundtable converged on topics like race, labor, and art. Chris Nealon (Johns Hopkins University) introduced his objects by asking probing questions about Marx and those who don’t have  a direct relation to the labor that produces their objects. Pointing out that “you never leave the theatre humming the critique,” Professor Nealon ceded his time to a song, “Are My Hands Clean?” by Sweet Honey in the Rock, an object that sparked much conversation during the Q&A. Richard Purcell (Carnegie Mellon University) was the only speaker to take a film as his object of critique, focusing on Charlie Ahearn’s 1979 “The Deadly Art of Survival.” Purcell presented the film itself as a critique, pointing to its use of blacksploitation tropes, scenes of leisure time, situation amongst a culture of collectivism, and presentation of singular heroism. Following this practice of amplifying an object’s critique, Amira Rose Davis (Penn State University) looked at black women athletes’ autobiographies. She presented a timeline of African American women in the Olympics and the groups that later used their bodies for commercial and political gains to argue that the US didn’t see black women athletes as threatening political beings during the Civil Rights era and beyond, and thus felt comfortable sending them abroad as international ambassadors.

a direct relation to the labor that produces their objects. Pointing out that “you never leave the theatre humming the critique,” Professor Nealon ceded his time to a song, “Are My Hands Clean?” by Sweet Honey in the Rock, an object that sparked much conversation during the Q&A. Richard Purcell (Carnegie Mellon University) was the only speaker to take a film as his object of critique, focusing on Charlie Ahearn’s 1979 “The Deadly Art of Survival.” Purcell presented the film itself as a critique, pointing to its use of blacksploitation tropes, scenes of leisure time, situation amongst a culture of collectivism, and presentation of singular heroism. Following this practice of amplifying an object’s critique, Amira Rose Davis (Penn State University) looked at black women athletes’ autobiographies. She presented a timeline of African American women in the Olympics and the groups that later used their bodies for commercial and political gains to argue that the US didn’t see black women athletes as threatening political beings during the Civil Rights era and beyond, and thus felt comfortable sending them abroad as international ambassadors.

Returning to Chris Nealon’s economic focus, Annie McClanahan (University of California, Irvine) considered  tip/gig work and the dilemma it presents for literary form. A growing type of labor in the US, tip work and gig work encourages more fluidity, experimental temporalities, and fractured relationships in contemporary narratives. Ebony Coletu (Penn State University) followed McClanahan by considering Fannie Lou Hamer’s speech about registering as a voter. Coletu presented voter registration forms as “the battleground for resources and access,” but also as a tool for shrinking black worlds. Chris Castiglia (Penn State University) concluded the roundtable with the provocation to view a critique as an implicit ideal. Castiglia presented William Mumler’s spirit photos and Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s candy sculptures to ask us to think about the roles belief, idealism, grief, and love play in our critique. Perhaps, Castiglia suggested, critics might invest a sense of belief and infinity in our objects.

tip/gig work and the dilemma it presents for literary form. A growing type of labor in the US, tip work and gig work encourages more fluidity, experimental temporalities, and fractured relationships in contemporary narratives. Ebony Coletu (Penn State University) followed McClanahan by considering Fannie Lou Hamer’s speech about registering as a voter. Coletu presented voter registration forms as “the battleground for resources and access,” but also as a tool for shrinking black worlds. Chris Castiglia (Penn State University) concluded the roundtable with the provocation to view a critique as an implicit ideal. Castiglia presented William Mumler’s spirit photos and Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s candy sculptures to ask us to think about the roles belief, idealism, grief, and love play in our critique. Perhaps, Castiglia suggested, critics might invest a sense of belief and infinity in our objects.

The day finished with a panel of graduate student symposium organizers who asked probing questions about  communities, activism, and the University. The following discussion remarked upon the ways the day’s events engaged with - and went beyond - the now-institutionalized practice of post-critique. And indeed they did. Unlike many other conversations in the recent past, Institutionally Speaking did not get hung up on debates about the crisis in the humanities or critique vs. post-critique. Participants presented stirring, challenging objects that helped to unsettle our notions of what the job of the critic is or should be. Critique means amplifying our objects, reconsidering our perceptions of knowledge-production, actively reforming and challenging our institutions, and finding the ideals buried within our engagements with art, literature, music, and technology.

communities, activism, and the University. The following discussion remarked upon the ways the day’s events engaged with - and went beyond - the now-institutionalized practice of post-critique. And indeed they did. Unlike many other conversations in the recent past, Institutionally Speaking did not get hung up on debates about the crisis in the humanities or critique vs. post-critique. Participants presented stirring, challenging objects that helped to unsettle our notions of what the job of the critic is or should be. Critique means amplifying our objects, reconsidering our perceptions of knowledge-production, actively reforming and challenging our institutions, and finding the ideals buried within our engagements with art, literature, music, and technology.