Radical Engagements: Speculative Fictions and Social Justice

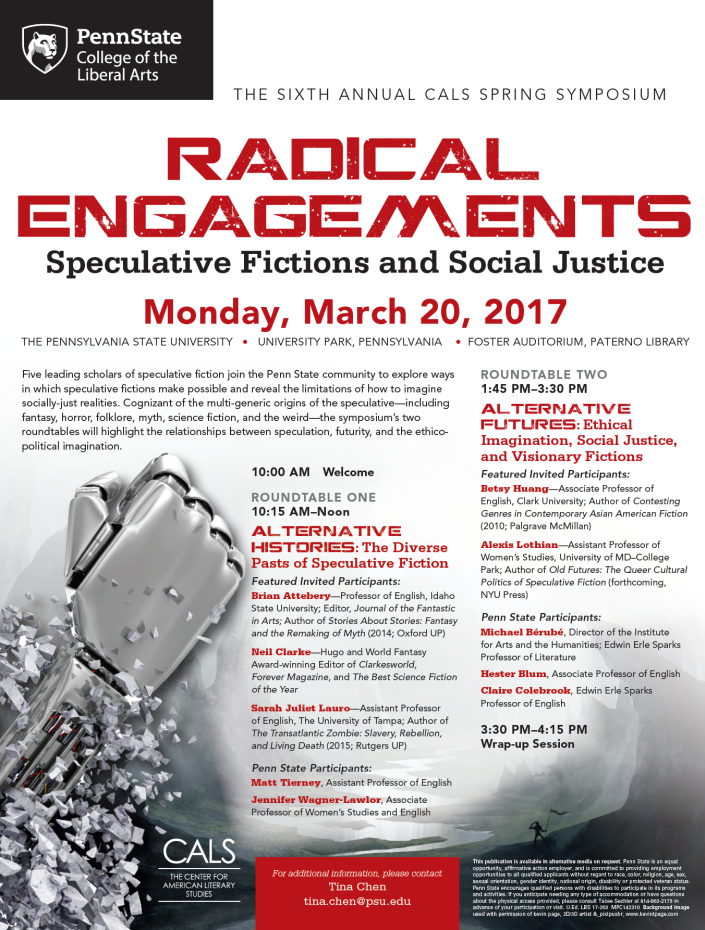

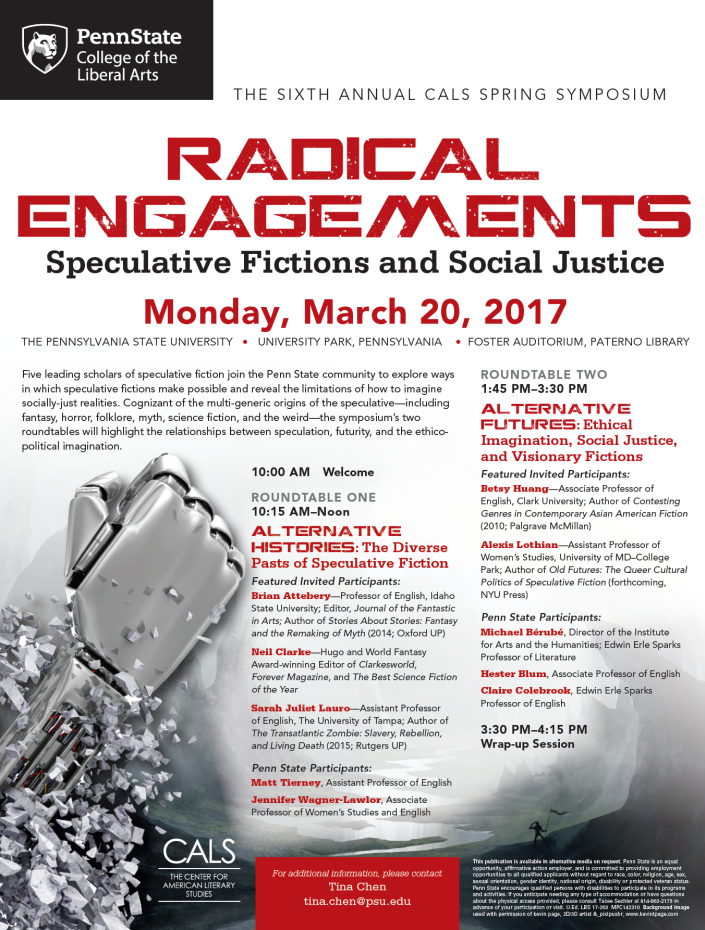

Despite what some might consider its humble origins in the “genre ghettos” of pulp magazines and dime novels, speculative fiction has proven to be a fruitful and nuanced literary mode with important implications for both social justice and the political imaginary. On Monday, March 20, the Center for American Literary Studies brought together ten leading thinkers from both Penn State and elsewhere around the country to explore the ways that speculative fictions reveal both the possibilities and limitations of how we imagine socially-just realities. The day-long event’s two roundtables were organized around temporal themes, focusing on both the alternative histories that speculative fictions make visible, and the alternative futures that it might make possible. This sixth annual CALS spring symposium was organized largely by the members of Tina Chen’s Fall 2016 Contemporary Speculative Fictions class (English 577), which focused on “the speculative” as both a literary mode and a critical approach. “Radical Engagements” thus sought to challenge easy generic distinctions (between science fiction, fantasy, horror, etc.), distinctions between genre fiction and “the literary,” and between simplistic separations of the utopic and dystopic.

The first roundtable, “Alternative Histories: The Diverse Pasts of Speculative Fictions,” highlighted the diverse origins of speculative fiction in order to theorize about its relationship to both past and present. How have these fictions changed over time? Must the speculative involve the future, or might it also be an act of recovery? What the speakers in this roundtable revealed is that, much like the future, history is also always speculative, and this historical speculation is vital for envisioning alternative political relations in the present. The roundtable began with Neil Clarke, Hugo and World Fantasy Award-winning editor of Clarkesworld. Clarke emphasized the importance of editors and publishers in shaping the direction and politics of the genre, both in terms of its content, themes, and tropes, and in the representation of authors along race and gender lines. Jennifer Wagner-Lawlor (Penn State) talked about the historical origins of the utopian story, arguing that its deferral of narrative closure expressed a desire for radical social or political alternatives, which served as a counter-point to the often-conservative form of the novel.

The first roundtable, “Alternative Histories: The Diverse Pasts of Speculative Fictions,” highlighted the diverse origins of speculative fiction in order to theorize about its relationship to both past and present. How have these fictions changed over time? Must the speculative involve the future, or might it also be an act of recovery? What the speakers in this roundtable revealed is that, much like the future, history is also always speculative, and this historical speculation is vital for envisioning alternative political relations in the present. The roundtable began with Neil Clarke, Hugo and World Fantasy Award-winning editor of Clarkesworld. Clarke emphasized the importance of editors and publishers in shaping the direction and politics of the genre, both in terms of its content, themes, and tropes, and in the representation of authors along race and gender lines. Jennifer Wagner-Lawlor (Penn State) talked about the historical origins of the utopian story, arguing that its deferral of narrative closure expressed a desire for radical social or political alternatives, which served as a counter-point to the often-conservative form of the novel.

Sarah Juliet Lauro (University of Tampa) focused her remarks on the figure of the zombie, America’s legacy of racialized slavery, and the possibilities of thinking “histories that weren’t.” Moving through texts like Colson Whitehead’s Zone One (2011) and The Underground Railroad (2016) beside Octavia Butler’s classic novel of historical speculative fiction, Kindred (1979), Lauro’s presentation directed scholars toward rethinking the gap between history and our representations of it as a “productive absence” that reveals our alternative pasts and presents. Matt Tierney (Penn State) described speculative fiction as a “strategic vantage point,” a place to stand, from which we might “wield the conceptual tools of the past” not in pursuit of the future, but in defiance of it, seeking instead a liberating version of the present. Brian Attebery (Idaho State University), like Lauro, focused his remarks on the “gaps” or unknowns of history as spaces that speculative fiction might fill with alternative and situated narratives of the past. Fantasy in particular, he argued, demonstrates that “there is more than one history of the world.”

Sarah Juliet Lauro (University of Tampa) focused her remarks on the figure of the zombie, America’s legacy of racialized slavery, and the possibilities of thinking “histories that weren’t.” Moving through texts like Colson Whitehead’s Zone One (2011) and The Underground Railroad (2016) beside Octavia Butler’s classic novel of historical speculative fiction, Kindred (1979), Lauro’s presentation directed scholars toward rethinking the gap between history and our representations of it as a “productive absence” that reveals our alternative pasts and presents. Matt Tierney (Penn State) described speculative fiction as a “strategic vantage point,” a place to stand, from which we might “wield the conceptual tools of the past” not in pursuit of the future, but in defiance of it, seeking instead a liberating version of the present. Brian Attebery (Idaho State University), like Lauro, focused his remarks on the “gaps” or unknowns of history as spaces that speculative fiction might fill with alternative and situated narratives of the past. Fantasy in particular, he argued, demonstrates that “there is more than one history of the world.”

The second roundtable, “Alternative Futures: Ethical Imagination, Social Justice, and Visionary Fictions,” focused on the complicated relationship between the imagined futures of speculative fictions and the ethical demands of the present in which they are embedded. Michael Bérubé (Penn State) began this session with the question, “Why is it so hard to imagine a positive future?” He described a film series hosted by the Institute for the Arts and Humanities at Penn State entitled “Bad Futures,” which presented fifteen films (such as Blade Runner, Children of Men, Gattaca, and 28 Days Later) in three days, all of which depict dystopian or apocalyptic visions of the future. Betsy Huang (Clark University) returned the conversation to the figure of the zombie, here in the context of plague fiction and its relationship with race. Huang described the ambivalence of plague narratives that present a “post-racial” future while also demonstrating the horror of “deathly sameness” in a figure like the zombie. These narratives, she argued, force us to confront the consequences of an “anemic imagination” that cannot articulate a radical alternative for the future, thus demanding an “ethics after cynicism” that challenges insidious versions of whiteness “disguised as the harbinger of a raceless future” that are present in contemporary culture.

The second roundtable, “Alternative Futures: Ethical Imagination, Social Justice, and Visionary Fictions,” focused on the complicated relationship between the imagined futures of speculative fictions and the ethical demands of the present in which they are embedded. Michael Bérubé (Penn State) began this session with the question, “Why is it so hard to imagine a positive future?” He described a film series hosted by the Institute for the Arts and Humanities at Penn State entitled “Bad Futures,” which presented fifteen films (such as Blade Runner, Children of Men, Gattaca, and 28 Days Later) in three days, all of which depict dystopian or apocalyptic visions of the future. Betsy Huang (Clark University) returned the conversation to the figure of the zombie, here in the context of plague fiction and its relationship with race. Huang described the ambivalence of plague narratives that present a “post-racial” future while also demonstrating the horror of “deathly sameness” in a figure like the zombie. These narratives, she argued, force us to confront the consequences of an “anemic imagination” that cannot articulate a radical alternative for the future, thus demanding an “ethics after cynicism” that challenges insidious versions of whiteness “disguised as the harbinger of a raceless future” that are present in contemporary culture.

Claire Colebrook (Penn State) reflected on the term speculation itself in its financial, philosophical, and fictional contexts that emerged in the late nineteenth century. The term, she argued, always exists in a double sense: as a grasp of the whole and an opening to the future, but one which also sacrifices the present and the local in the name of that future. In all forms of speculation, then, futurity itself might be read as ambivalent, if not inherently dangerous. Hester Blum (Penn State)  examined Rachel Carson’s 1951 The Sea Around Us in relation to the work of Ursula LeGuin’s 1974 novel The Dispossessed to rethink the relationship between the human and “the oceanic” in light of climate change and the Anthropocene. Rather than the rhythm of cyclical return that Carson describes in her book, Blum argued that LeGuin’s notion of a planetary perspective of “continually decentered spiralizing motion” might offer us a new way of thinking our relationship to both earth and sea. Finally, Alexis Lothian (University of Maryland, College Park) discussed speculative fiction in relation to queer possibility. Like Colebrook and Tierney, Lothian described an ambivalence toward futurity, particularly as it is often figured in science fiction, as a concept entangled with racialized heteronormativity, capitalism, and cultural colonization. While “it isn’t easy to leave the future behind,” she noted, fictional futures might also provide experimental sites for working out “radically speculative temporalities,” or “queer temporalities,” that resist the more conservative futures of traditional science fiction.

examined Rachel Carson’s 1951 The Sea Around Us in relation to the work of Ursula LeGuin’s 1974 novel The Dispossessed to rethink the relationship between the human and “the oceanic” in light of climate change and the Anthropocene. Rather than the rhythm of cyclical return that Carson describes in her book, Blum argued that LeGuin’s notion of a planetary perspective of “continually decentered spiralizing motion” might offer us a new way of thinking our relationship to both earth and sea. Finally, Alexis Lothian (University of Maryland, College Park) discussed speculative fiction in relation to queer possibility. Like Colebrook and Tierney, Lothian described an ambivalence toward futurity, particularly as it is often figured in science fiction, as a concept entangled with racialized heteronormativity, capitalism, and cultural colonization. While “it isn’t easy to leave the future behind,” she noted, fictional futures might also provide experimental sites for working out “radically speculative temporalities,” or “queer temporalities,” that resist the more conservative futures of traditional science fiction.

Like former CALS spring symposia, “Radical Engagements” served the important purpose of bringing together a variety of American literature scholars at different points in their careers into a single conversation. The wrap-up session featured graduate student respondents who synthesized many of the important points raised by the panelists, and then posed a series of questions. This synthesis opened the floor to a dynamic discussion between audience members, graduate students, and panelists on the radical possibilities of speculative fiction. Participants concluded that speculative fiction serves as not only a complex and historically rich literary mode, but also as a tool or reading practice that might harness the power of the imagination in the service of the socially just.

Like former CALS spring symposia, “Radical Engagements” served the important purpose of bringing together a variety of American literature scholars at different points in their careers into a single conversation. The wrap-up session featured graduate student respondents who synthesized many of the important points raised by the panelists, and then posed a series of questions. This synthesis opened the floor to a dynamic discussion between audience members, graduate students, and panelists on the radical possibilities of speculative fiction. Participants concluded that speculative fiction serves as not only a complex and historically rich literary mode, but also as a tool or reading practice that might harness the power of the imagination in the service of the socially just.

Despite what some might consider its humble origins in the “genre ghettos” of pulp magazines and dime novels, speculative fiction has proven to be a fruitful and nuanced literary mode with important implications for both social justice and the political imaginary. On Monday, March 20, the Center for American Literary Studies brought together ten leading thinkers from both Penn State and elsewhere around the country to explore the ways that speculative fictions reveal both the possibilities and limitations of how we imagine socially-just realities. The day-long event’s two roundtables were organized around temporal themes, focusing on both the alternative histories that speculative fictions make visible, and the alternative futures that it might make possible. This sixth annual CALS spring symposium was organized largely by the members of Tina Chen’s Fall 2016 Contemporary Speculative Fictions class (English 577), which focused on “the speculative” as both a literary mode and a critical approach. “Radical Engagements” thus sought to challenge easy generic distinctions (between science fiction, fantasy, horror, etc.), distinctions between genre fiction and “the literary,” and between simplistic separations of the utopic and dystopic.

The first roundtable, “Alternative Histories: The Diverse Pasts of Speculative Fictions,” highlighted the diverse origins of speculative fiction in order to theorize about its relationship to both past and present. How have these fictions changed over time? Must the speculative involve the future, or might it also be an act of recovery? What the speakers in this roundtable revealed is that, much like the future, history is also always speculative, and this historical speculation is vital for envisioning alternative political relations in the present. The roundtable began with Neil Clarke, Hugo and World Fantasy Award-winning editor of Clarkesworld. Clarke emphasized the importance of editors and publishers in shaping the direction and politics of the genre, both in terms of its content, themes, and tropes, and in the representation of authors along race and gender lines. Jennifer Wagner-Lawlor (Penn State) talked about the historical origins of the utopian story, arguing that its deferral of narrative closure expressed a desire for radical social or political alternatives, which served as a counter-point to the often-conservative form of the novel.

The first roundtable, “Alternative Histories: The Diverse Pasts of Speculative Fictions,” highlighted the diverse origins of speculative fiction in order to theorize about its relationship to both past and present. How have these fictions changed over time? Must the speculative involve the future, or might it also be an act of recovery? What the speakers in this roundtable revealed is that, much like the future, history is also always speculative, and this historical speculation is vital for envisioning alternative political relations in the present. The roundtable began with Neil Clarke, Hugo and World Fantasy Award-winning editor of Clarkesworld. Clarke emphasized the importance of editors and publishers in shaping the direction and politics of the genre, both in terms of its content, themes, and tropes, and in the representation of authors along race and gender lines. Jennifer Wagner-Lawlor (Penn State) talked about the historical origins of the utopian story, arguing that its deferral of narrative closure expressed a desire for radical social or political alternatives, which served as a counter-point to the often-conservative form of the novel.

Sarah Juliet Lauro (University of Tampa) focused her remarks on the figure of the zombie, America’s legacy of racialized slavery, and the possibilities of thinking “histories that weren’t.” Moving through texts like Colson Whitehead’s Zone One (2011) and The Underground Railroad (2016) beside Octavia Butler’s classic novel of historical speculative fiction, Kindred (1979), Lauro’s presentation directed scholars toward rethinking the gap between history and our representations of it as a “productive absence” that reveals our alternative pasts and presents. Matt Tierney (Penn State) described speculative fiction as a “strategic vantage point,” a place to stand, from which we might “wield the conceptual tools of the past” not in pursuit of the future, but in defiance of it, seeking instead a liberating version of the present. Brian Attebery (Idaho State University), like Lauro, focused his remarks on the “gaps” or unknowns of history as spaces that speculative fiction might fill with alternative and situated narratives of the past. Fantasy in particular, he argued, demonstrates that “there is more than one history of the world.”

Sarah Juliet Lauro (University of Tampa) focused her remarks on the figure of the zombie, America’s legacy of racialized slavery, and the possibilities of thinking “histories that weren’t.” Moving through texts like Colson Whitehead’s Zone One (2011) and The Underground Railroad (2016) beside Octavia Butler’s classic novel of historical speculative fiction, Kindred (1979), Lauro’s presentation directed scholars toward rethinking the gap between history and our representations of it as a “productive absence” that reveals our alternative pasts and presents. Matt Tierney (Penn State) described speculative fiction as a “strategic vantage point,” a place to stand, from which we might “wield the conceptual tools of the past” not in pursuit of the future, but in defiance of it, seeking instead a liberating version of the present. Brian Attebery (Idaho State University), like Lauro, focused his remarks on the “gaps” or unknowns of history as spaces that speculative fiction might fill with alternative and situated narratives of the past. Fantasy in particular, he argued, demonstrates that “there is more than one history of the world.”

The second roundtable, “Alternative Futures: Ethical Imagination, Social Justice, and Visionary Fictions,” focused on the complicated relationship between the imagined futures of speculative fictions and the ethical demands of the present in which they are embedded. Michael Bérubé (Penn State) began this session with the question, “Why is it so hard to imagine a positive future?” He described a film series hosted by the Institute for the Arts and Humanities at Penn State entitled “Bad Futures,” which presented fifteen films (such as Blade Runner, Children of Men, Gattaca, and 28 Days Later) in three days, all of which depict dystopian or apocalyptic visions of the future. Betsy Huang (Clark University) returned the conversation to the figure of the zombie, here in the context of plague fiction and its relationship with race. Huang described the ambivalence of plague narratives that present a “post-racial” future while also demonstrating the horror of “deathly sameness” in a figure like the zombie. These narratives, she argued, force us to confront the consequences of an “anemic imagination” that cannot articulate a radical alternative for the future, thus demanding an “ethics after cynicism” that challenges insidious versions of whiteness “disguised as the harbinger of a raceless future” that are present in contemporary culture.

The second roundtable, “Alternative Futures: Ethical Imagination, Social Justice, and Visionary Fictions,” focused on the complicated relationship between the imagined futures of speculative fictions and the ethical demands of the present in which they are embedded. Michael Bérubé (Penn State) began this session with the question, “Why is it so hard to imagine a positive future?” He described a film series hosted by the Institute for the Arts and Humanities at Penn State entitled “Bad Futures,” which presented fifteen films (such as Blade Runner, Children of Men, Gattaca, and 28 Days Later) in three days, all of which depict dystopian or apocalyptic visions of the future. Betsy Huang (Clark University) returned the conversation to the figure of the zombie, here in the context of plague fiction and its relationship with race. Huang described the ambivalence of plague narratives that present a “post-racial” future while also demonstrating the horror of “deathly sameness” in a figure like the zombie. These narratives, she argued, force us to confront the consequences of an “anemic imagination” that cannot articulate a radical alternative for the future, thus demanding an “ethics after cynicism” that challenges insidious versions of whiteness “disguised as the harbinger of a raceless future” that are present in contemporary culture.

Claire Colebrook (Penn State) reflected on the term speculation itself in its financial, philosophical, and fictional contexts that emerged in the late nineteenth century. The term, she argued, always exists in a double sense: as a grasp of the whole and an opening to the future, but one which also sacrifices the present and the local in the name of that future. In all forms of speculation, then, futurity itself might be read as ambivalent, if not inherently dangerous. Hester Blum (Penn State)  examined Rachel Carson’s 1951 The Sea Around Us in relation to the work of Ursula LeGuin’s 1974 novel The Dispossessed to rethink the relationship between the human and “the oceanic” in light of climate change and the Anthropocene. Rather than the rhythm of cyclical return that Carson describes in her book, Blum argued that LeGuin’s notion of a planetary perspective of “continually decentered spiralizing motion” might offer us a new way of thinking our relationship to both earth and sea. Finally, Alexis Lothian (University of Maryland, College Park) discussed speculative fiction in relation to queer possibility. Like Colebrook and Tierney, Lothian described an ambivalence toward futurity, particularly as it is often figured in science fiction, as a concept entangled with racialized heteronormativity, capitalism, and cultural colonization. While “it isn’t easy to leave the future behind,” she noted, fictional futures might also provide experimental sites for working out “radically speculative temporalities,” or “queer temporalities,” that resist the more conservative futures of traditional science fiction.

examined Rachel Carson’s 1951 The Sea Around Us in relation to the work of Ursula LeGuin’s 1974 novel The Dispossessed to rethink the relationship between the human and “the oceanic” in light of climate change and the Anthropocene. Rather than the rhythm of cyclical return that Carson describes in her book, Blum argued that LeGuin’s notion of a planetary perspective of “continually decentered spiralizing motion” might offer us a new way of thinking our relationship to both earth and sea. Finally, Alexis Lothian (University of Maryland, College Park) discussed speculative fiction in relation to queer possibility. Like Colebrook and Tierney, Lothian described an ambivalence toward futurity, particularly as it is often figured in science fiction, as a concept entangled with racialized heteronormativity, capitalism, and cultural colonization. While “it isn’t easy to leave the future behind,” she noted, fictional futures might also provide experimental sites for working out “radically speculative temporalities,” or “queer temporalities,” that resist the more conservative futures of traditional science fiction.

Like former CALS spring symposia, “Radical Engagements” served the important purpose of bringing together a variety of American literature scholars at different points in their careers into a single conversation. The wrap-up session featured graduate student respondents who synthesized many of the important points raised by the panelists, and then posed a series of questions. This synthesis opened the floor to a dynamic discussion between audience members, graduate students, and panelists on the radical possibilities of speculative fiction. Participants concluded that speculative fiction serves as not only a complex and historically rich literary mode, but also as a tool or reading practice that might harness the power of the imagination in the service of the socially just.

Like former CALS spring symposia, “Radical Engagements” served the important purpose of bringing together a variety of American literature scholars at different points in their careers into a single conversation. The wrap-up session featured graduate student respondents who synthesized many of the important points raised by the panelists, and then posed a series of questions. This synthesis opened the floor to a dynamic discussion between audience members, graduate students, and panelists on the radical possibilities of speculative fiction. Participants concluded that speculative fiction serves as not only a complex and historically rich literary mode, but also as a tool or reading practice that might harness the power of the imagination in the service of the socially just.